Until recently, the CLM team had a straightforward way of offering new members their choice of enterprises. We had a menu of two-item choices. A member could pick from among goats, pigs, poultry, small commerce, and agriculture, and each would pick two. We are much more flexible now, but in our early years, we were quite rigid. It made a complex part of our work manageable.

But there were occasional exceptions. Ti Manman was one.

“Ti manman” means “Little Mama,” and it is what most people call Simélia Duvelsaint.

When she started the program, she had nothing. “A neighbor was letting me raise his sow, and he would have had to give me a piglet, but he took it back before it gave birth, so I got nothing.”

She and her daughters were living in a straw shack. She supported them partly through small commerce. A neighbor would lend her money now and again, and she’d use it to buy used clothing, which she’d then sell at the Mache Kana market nearby. She had learned to sew as a young girl, so when she found a tailor who would sometimes let her use her sewing machine, she became capable of altering the clothes for her clients, too. Occasionally, she’d even get the chance to make a uniform or two for schoolchildren.

It was, however, unreliable work because anytime the tailor went anywhere, Simélia would find the door locked, and she’d just have to go back home. “I couldn’t say anything. The woman wasn’t charging me. She was just letting me use her machine to be nice. She saw how difficult things were for me.”

Simélia had learned to sew by investing in her own education, something she started to do as a young girl. When she saw that her parents wouldn’t send her to school, she started earning money herself, grating manioc for neighbors who were making kasav, a Haitian flat bread. She used her earning to pay someone to teach her to read and write. “I never went to school, but I got up to the fourth-grade level. Now I’m one of the readers in my church, and I’m the one who works with my granddaughter.” She then found a tailor, and paid her to teach her the trade. “It didn’t cost much back then.”

She never had her own sewing machine, but she started to succeed. She saved enough to buy a cow, which she eventually sold to buy a small piece of land from a neighbor. But she never got to use the land, because one of the seller’s siblings took it away from her. “I had no one to help me,” she explains. She was left with the cow’s calf, but someone in the neighborhood broke its leg with a rock, and it eventually died.

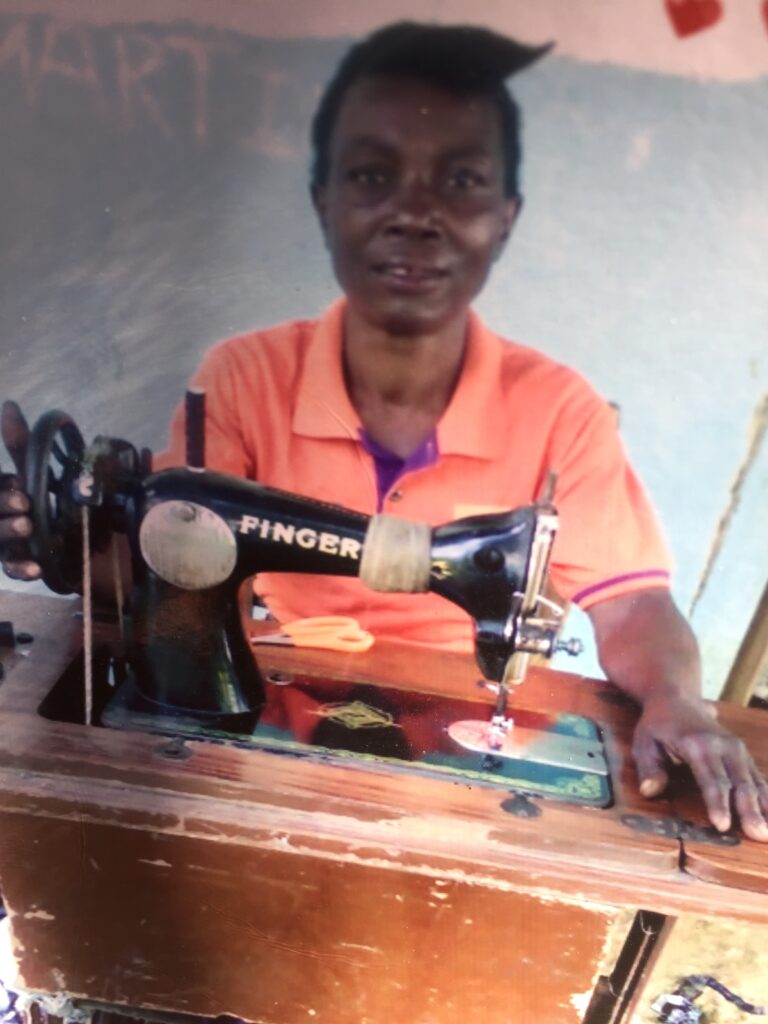

When she joined CLM, she chose goats and small commerce, but at one of the first days of training, the staff asked whether there was anyone who knew how to sew, “and I raised my hand.” Her case manager, Martinière, used the money he would have used to buy her goats and small commerce towards buying a sewing machine, instead. “It wasn’t quite enough,” he explained. “We had to use money she had saved from her weekly stipend, too.”

But she got the machine, and started to work. “I saved as much as I could after paying for the girls’ school, and I started to buy goats. I eventually had seven, but they got sick and died.” She’s had more success with pigs. She now has two: a full-grown sow and a younger one. She also gave her younger daughter one of the sow’s daughters to raise, and her daughter’s sow is now pregnant, almost ready to give birth.

Though her older daughter moved out in July, Simélia still has two children with her: her younger daughter and that daughter’s little girl. And until this year, the sewing machine was the key to their income. But it’s been broken for about six months. The only repairman she could find tried replacing some parts, but it didn’t do the trick. She’s waiting for him to come try something else.

In the meantime, she’s selling used clothing again. She also sells laye, a platter woven of straw used in various ways in the countryside. Finally, she sells bowls made of gourds, which are used in Vodoun ceremonies. She goes to four different markets every week. Her income varies, but she uses a sòlto steady herself. She and about ten other women contribute 500 gourds, or about $5.50, a week, and each week one woman takes the whole pot. “When it is my turn, I can use the money to buy poultry, to invest in my businesses, and to pay back any debts I have.”

Simélia continues to work hard. She invests a lot in her children’s education. But she also has a dream. She would like, once more, to buy a cow. “It’s just something I’ve always wanted.”