Vunet Jean is seventeen. He’s from Lower Koladè, a small, extremely rural area of the Central Plateau. Koladè itself is small and rural, about an hour’s drive over a bad section of Route 3 that heads north out of Ench. Lower Koladè is a modest walk to the west, a walk down a hill, off the highway.

Vunet came to Pòtoprens with his aunt, Jidit, the mother of my godson, Givens. She spent a month in the countryside with her boys this summer, wanting to get away from the city and to make sure her sons come to know both the part of Haiti that they come from and their family. Her father-in-law, Marinot, lives in a house along the main road in Koladè itself, but she spent her time at her own parents’ house, well off the road in nearby Kalifòn.

Jidit is the fourth of her parents’ eight surviving children: seven daughters and a son. Saül, her husband, is one of seven children, so their boys have lots of family to get to know. Vunet is her oldest sister’s oldest son. He would be the oldest child of his generation except that his sister, Vunette, is a few minutes older than he is. They’re twins.

I don’t know how the discussions went that led to Vunet coming to Pòtoprens with his aunt, but I know a couple of things. Vunet had just taken the national primary school graduation exam. He and his sister both had. They had taken it for the second time, having both failed it the previous year. They repeated sixth grade after the failure, the first that either of them had ever experienced, and were waiting for the results. Pass or fail, their parents had decided that they could not pay for more education. They have five younger siblings who need to go to school as well. They arranged to send Vunette to stay with relatives in Tomonn, a small city south of Ench. She was going to learn dressmaking. Vunet would spend the fall with Jidit, and then go to Okap in December. His uncle, Jidit’s one brother, lives there. He’s Vunet’s godfather, and their family decided to send Vunet to live with him. He would try to help young Vunet find work.

It took unusually long for the results of the exam for kids in the Ench region to be published. It was a couple of weeks after al the results for other parts of the country had been published that we learned that Vunet had failed, as had everyone from his school. For that matter, so had all but one of the kids from the other school in Koladè. So Vunet resigned himself to moving on with his life without graduating from sixth grade.

But Jidit was not so ready to let it go at that. She had found over the course of a couple of weeks that she and her children very much like having Vunet around, so she started to think about sending him to school for a third attempt at sixth grade. Her youngest sister, Amiz, had just passed the exam after spending the past year attending a school not far from Jidit’s home. Amiz was in her mid-twenties, and had given up on school years before until she returned with Jidit’s encouragement. Jidit imagined that there was no reason Vunet could not succeed as well.

I don’t know how much schooling Jidit herself had. She can read Creole slowly, and sign her name. She’s able to help her boys with their preschool homework. But she cannot have gotten very far. Nevertheless – or maybe just for that reason – she is devoted to her children’s education and to education for other young people that come under her influence.

So she registered Vunet for school, promising the principal that she’d bring him the documents about Vunet – birth certificate, last year’s report card – as soon as they can be sent in from the countryside. She started going about arranging for Vunet’s uniform and for him books.

In the meantime, she and I decided that Vunet would come up the mountain and spend a weekend with me in Kaglo. We thought he’d enjoy a couple days in the countryside, especially since there’d be boys his own age for him to meet and hang around with. We imagined that, as good as he is with his little cousins, who are six and three, he might need a change of pace. Jidit knew that she could count on Madanm Anténor to welcome him warmly, which is to say that she knew he would not be hungry. Vunet himself was pleased about the plan.

We went up the hill Saturday afternoon, arriving rather late because a heavy rain had stopped us on the way. We went straight to meet Madanm Anténor. I knew that, once she knew he was with me, his weekend would be as good as arranged. We also wanted to talk to Mèt Anténor. As the principal of a public primary school, he knows a lot about the exam and about helping kids pass it. As miserable as the resources available to his school are, a very high percentage of kids always pass. So we wanted to ask his advice.

I was a little puzzled by then. I had spent enough time with Vunet to judge that he is a bright and serious young man. I did some basic math with him because it was something we could do together and I was curious as to his level, and I was impressed with how quickly he caught on to things he had not previously seen. I couldn’t quite figure how he failed the exam not once but twice. After a few minutes questioning, however, Mèt Anténor was able to make the picture very clear.

Most schools in Haiti are private businesses. Their owners’ profits can be affected by anything that affects their reputations, and perhaps nothing could affect a small primary school’s reputation more than the success of its students in the exam. The year Vunet took the exam the first time, his classmates had done poorly. Apparently, the principal tried to dramatically change that, and his effort backfired. The story that Mèt Anténor pieced together suggests that he arranged for his students to cheat, that they were caught, and that the result was disastrous for the kids. This requires some explanation.

The exam papers are centrally graded by teams of teachers whom the government pays to do the job. Answer sheets have neither the student’s name nor the school’s name on them. They are anonymous. But it’s not unusual for a principal to have connections to a teacher who’s grading papers. The principal can have his or her students leave a pre-arranged mark on their answer sheet. The grader sees the mark, and gives the student as high a grade as he or she can. There is a certain amount of leeway in the way points are allotted because partial credit is awarded for answers that are partially correct. So a well-disposed grader can have a big impact on an individual student or on a group of kids from a single school.

If, however, the wrong person – maybe I should rather say the right person – sees that the answer sheets have a suspicious mark on them, a whole school’s pile of answer sheets can be thrown out. Everyone fails. And that is what Mèt Anténor suspects. Vunet himself reported that one of his teachers had been hired to work as part of the correction team and that their principal had taught the kids in their school to mark their sheets a certain way.

So Vunet was instructed by his principal to cheat, and now he is paying the consequences. Though I’m sure he wishes he had passed the exam, he doesn’t seem discouraged, and he seems excited about the chance that Jidit is providing. He also tells me that he likes staying with Jidit, Saül, and their boys. His parents have agreed to postpone any thought of sending him to his uncle in Okap. I suppose that they’re excited about this new opportunity as well. When I asked Vunet what he wants to do when he passes the exam next year – and I very much believe he will – he said he wants to go on to seventh grade. That is still a year away, a long time in the life of a seventeen-year-old boy, but he didn’t show any sign of doubt. Like many Haitians he is excited about any chance for education. I’m excited for him as well.

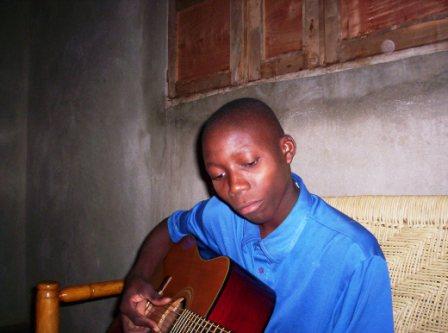

Here’s a picture of Vunet that I took while he was up in Kaglo.

Vunet