As we start our weekly visits with our new CLM members, we begin to face new issues. Each member has a story. Each faces her own set of difficulties. Our case managers’ first challenge is to get the members to share the problems they face, to talk about them frankly. That’s when our real work begins. Helping extremely poor women begin to strategize about their lives, helping them to look at their lives as something they can change, is the key to everything we do.

Licia lives in Chipen, in the corner of Tit Montay farthest from our base in Zaboka. Her home is high on a ridge that divides Boukankare from Ench, one of its neighbors to the north. The hike up to Zaboka from Viyèt, where we leave our motorcycles, is already almost four hours. Our team makes that trip every Sunday afternoon. On Monday morning, Martinière leaves early from Zaboka to walk to Chipen, almost two and a half hours away through the hills. He is Licia’s case manager, and he starts with her first, because she is the farthest of all. Then he works his way back downhill towards the lower end of Chipen before he hikes back to Zaboka.

When we got to Licia’s house, she announced that she was leaving the program. Martinière asked her why, and what she said shocked us. She’s cursed. The people around her hate her and will block her. Nothing can change her life.

By way of explanation, she told us the following story: For the first six months that CLM members spend in the program, we give them a small cash stipend, just a little more than a dollar per day. It’s designed as a way to protect their new assets. As small as it is, it helps them guarantee that they can feed themselves and their children without selling the animals we give them or reaching too deeply into the commerce they’re trying to build up. Our expectation is that by the time they’ve spent six months in the program, their assets will be earning them enough income to do the work the stipend has been doing.

But many of the women choose to invest these stipends rather than spending them just to buy food. They buy livestock, mostly fowl. It’s not really what the stipends are intended for, but we are so glad to see the women thinking in terms of investment, that we don’t worry too much. We just try to see to it that they have something to feed their kids as well.

Licia decided to buy a turkey. It would be a big investment, but it could pay off handsomely. Turkeys are hardier than chickens, and this is a major consideration this time of year, when many chickens die in the relatively cold weather. Turkeys reproduce well, and are easy to sell for a decent price. So she went to the market in Nansab, in southern Ench, and bought a young female for 600 gourds, or two weeks’ stipend. She had a number of errands to run in the market, so she left her little boy to keep an eye on the turkey, and went her way.

Unfortunately, the little boy was more interested in a soccer match than in his mother’s new turkey. He went off to watch the match, and when his mother returned, the turkey was gone. She looked all over the market for it, but could find no trace. Her investment disappeared the same day she made it. She felt so discouraged by the loss that she decided to leave the program. There was no point in continuing. She was obviously cursed.

Fortunately, she was open to listening. Martinière talked a lot. But the heart of what he said was simple: She should look at the loss as a lesson. Her boy is not mature enough to be left with such a serious responsibility. Haitian’s say “se mèt kò a ki veye kò a.” This means that a body’s owner is the one who should keep an eye on it. Martinière encouraged her to realize that she herself must take responsibility for the decisions she makes and the assets they bring her way. But for her to leave the program right as it is starting would not solve anything. After some discussion, she relented. She will continue with us, maybe a little bit wiser for her loss.

The problem with Léonie is more serious. We are not sure we can keep her in the program because we can’t get her to tell us the truth. I’ve put together her story from evidence we’ve collected from her neighbors, including the local KASEK, the government official who resides in the zone.

Her partner, the father of her youngest child, is married to another woman. Léonie has been living in a small, dilapidated shack made of mud and sticks and covered with straw just a short distance from the man’s fairly nice house. One day, her partner was doing some work for her in her garden when his wife brought him a midday meal. Léonie was furious. She decided to leave him on the spot. So she left the house and went back to live with her mother.

This wouldn’t normally be a problem. It is not unusual for a CLM member to move. They do it from all sorts of reasons, including because they decide to break up with the man they’re with. But her mother lives well across the Boukankare border in Ench. While we plan to enter Ench eventually, we’re not working there yet. If that’s where Léonie lives, we can’t help her right now.

What’s worse, Léonie has been trying to hide what’s she’s doing from us. We know that she comes to the house she used to live in early on Monday morning so that she’ll be there when Martinière comes for his visit. Even if we had no other way of telling, the emptiness of the house and its yard speak volumes. But we’ve spoken to several witnesses as well who confirm that she doesn’t live there and that her children don’t either. She even borrowed a neighbor’s baby, claiming it to be her own, to show Martinière that they are both in the house. Unfortunately for her, Martinière was smart enough to catch her in the lie. For whatever reason, she is conspiring with the man she has left so that she can stay in the program and receive the assets that we offer.

But the situation really is complicated. We’ve heard that she isn’t actually at her mother’s house, either. We’ve heard that she has moved in with another man. The man lives in another area of Tit Montay, an area that we are currently serving. So it would resolve the problem if it turned out to be true. But until we can get her to speak clearly with us, we can’t move forward.

In the meantime, she and her partner are making visits to Chipen difficult for Martinière. They have spread the word that he comes carrying cash for CLM members, having the man’s older children loudly asking him to bring money to them, too. This makes the trip more dangerous than it needs to be.

For now, all I could tell her is that we can’t help her until we feel confident that we understand her situation. Her lies, I said, mean that we need to take more time. We have no choice. We have to put her on hold. Martinière will continue to visit her, but he will provide no stipend and give her no assets.

A third case: Tuesday morning, just after dawn, as the four Zaboka case managers and I were preparing to go our separate ways, an irate man came to see us. He is the partner of a new member from lower Zaboka. He told us the following story.

He has children by his wife, who is not the CLM member. One of his boys has a goat that he asked the CLM member to look after. When the boy risked being sent home from school because of non-payment of the tuition, the man decided he would have to sell the goat. It would be a big sacrifice because the goat was pregnant, but he felt he had no choice.

When he went to the CLM member to retrieve the goat, she refused to give it to him. She said that she had spoken to her case manager, Orweeth, and that he had told her that she could keep the goat and that he would arrange for her to get legal papers. The man said that, if that’s how CLM works, he would wreck the woman in CLM. Orweeth was there with us as the man spoke, and he gave every assurance that he had told the woman nothing of the kind. Orweeth promised to go by to see her at the end of the day.

As I was leaving Zaboka, I went by her home, and the man was there along with a crowd of neighbors. I asked the woman about it, and she denied outright that she had said any such thing. I told her in front of everyone that I did not automatically believe that she would say such a thing, but that since I wasn’t from the neighborhood, I couldn’t tell who was lying and who was telling the truth. But everyone should understand that CLM will be buying her two goats, but would never simply grant her possession of something that’s not hers.

The case is not simple, though. The woman explained that she has been together with the man for years, that they have children together, but that he’s never done anything for her. She pointed to her home, in terrible disrepair, and added that he hasn’t helped with her farming either. She was breaking up with him, but suggested that confiscating the goat was simply a matter of taking something she is owed. Normally she would receive a kid when the goat gives birth as the price of taking care of it for him. She feels understandably cheated. I asked her to talk about the problem with Orweeth when he comes by at the end of the day, and she said she would. An important part of our job is to ensure that our members get what is their right. We have to help them protect themselves from exploitation and abuse. But we have to find ways of doing so that make sense to the communities they live in.

Taking the man’s goat might be the right thing to do, but it will require discussion. That’s part of what we’re there for.

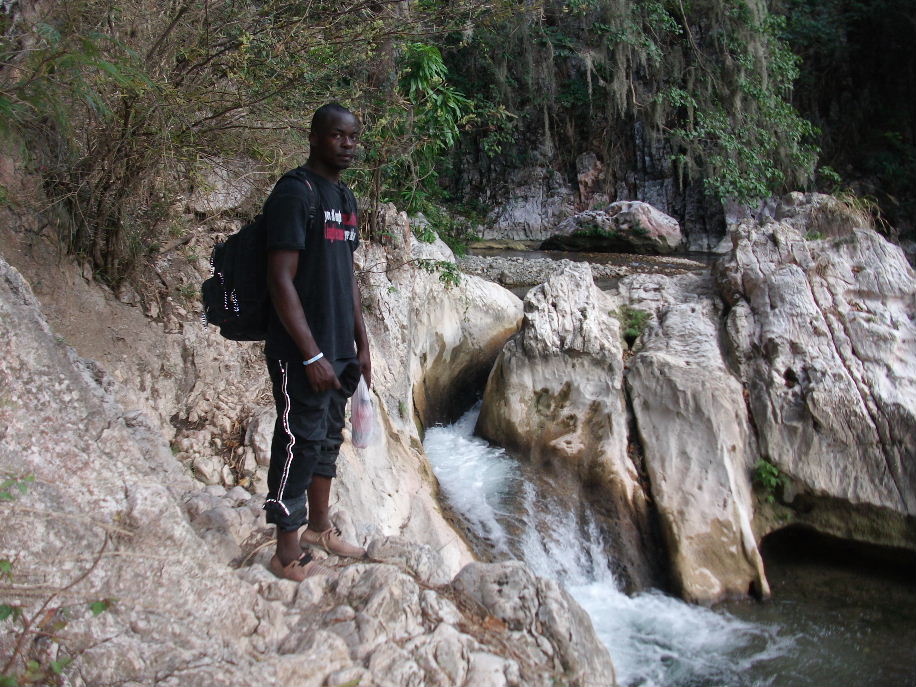

The hike to Zaboka is hard and long — almost four hours — but also lovely. It starts in the hilly farmland above Viyèt, and winds through Boukankola and Akildiso. It then threads a narrow pass alongside a waterfall. After that, it climbs up and down the steep, narrow slopes that cut through Tit Montay. The pictures below were taken next to the waterfall. Martinière Jasmin, whom I photographed, took the picture of me.