The mountaintop chapel in Piton, a very rural community within Fondwa, was badly damaged by January’s earthquake. About a third of the back wall remains, just a triangle of cinder blocks covering the lower left-hand corner. As you look behind the pulpit, you see a plantain grove and fruit trees through the space where the wall once was. The chapel’s important support posts are mostly intact, the poured concrete broken, and the iron cabling that strengthens it bent but still strong. The other walls, though cracked, still mostly stand, but sitting within the chapel you feel as though you are in a ruin, a ruin still doing the work it was built to do.

Fondwa, in mountainous southeastern Haiti, is about four hours away from the region where we do our work. The CLM team went there to attend a funeral. Franck Laurore, one of our new case managers, was killed on the job last Thursday.

Laurore was part of a team of four who had been assigned to collect data in an area called “Tifon.” Tifon is on the far side of the lake in Peligre that was formed when a hydroelectric dam was built in the 50s. The team had been working there for several days. Like the other teams that are in the field right now, they were following up community meetings, identifying the families who are poor enough to need our help.

Each day, three of them would take a canoe-ferry over and back across the lake while Laurore would walk. The extra hike would take him over an hour each way, but Laurore couldn’t swim, so he was afraid of the boats. Most of them are dugout canoes no reasonable person would believe in. All that extra walking makes a big difference in a day’s already hard fieldwork, but Laurore was simply afraid.

Thursday, he was exhausted. The team had been hiking all day up and down Tifon’s steep hills. They ran out off water and had nothing to eat. When they got back to the lake at the end of the day, his partners were surprised to see Laurore negotiating the price of the crossing with the oarsman. He was just too tired for the extra hike.

They got most of the way across the lake when a freak storm appeared. Its high winds swamped the boat. Two of the team members were able to swim to safety. A third man, who cannot swim, was saved because the wind blew them so close to the dam that a bystander was able to climb down and throw him something to grab hold of. Laurore panicked and went straight to the bottom. We recovered his body two days later, when it finally floated to the surface, just a few feet from the dam.

Laurore was 29, his aging parents’ sixth and youngest child. Our team met to plan the funeral with the older sister and brother-in-law whom he lived with while he went to high school. They had lots of understandable questions about their little brother’s death, but the most striking thing about the meeting was their very vocal determination that Laurore’s work continue. Even in his first months with the team he had apparently told them enough about what we do, enough about the desperate poverty of those we serve, to convince them of the work’s importance.

And the work is continuing. By Tuesday all the teams but Laurore’s were back in the field. Two of that team’s three surviving members are still too shaken to work, but the other was studying the remains of their soaked-through documents to determine what of their data can be salvaged and what must be collected all over again.

Our team’s members have been very badly shaken. But their determination is keeping them on the job nonetheless. César, another of the new case managers, explained this well. He talked to me about a woman he met on Tuesday, pregnant and living with three children on a straw mat on the floor of an open lean-to shack. She had found nothing to feed her kids that morning and wasn’t sure what she would give them the rest of the day. “When you see the way a woman like her is forced to live,” he said, “it’s easy to keep your mind on the job you need to do.”

Laurore’s death will change the way we do our work. It must. Although we know we will lose some of our program participants – their intense poverty can be deadly in any number of ways – we don’t expect to lose staff. They are healthy, strong young people. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be capable of doing this job. We must protect them. Lifejackets, which we should have had already, are now on the way. While we’re at it, we’ll be more insistent about the helmets that our staff is supposed to wear on motorcycles as well. One gets too accustomed to risk, too comfortable with it, and we simply have to be more aware of the safety issues that surround us. Laurore’s death robbed us of our most precious resource. We can let nothing like it happen again.

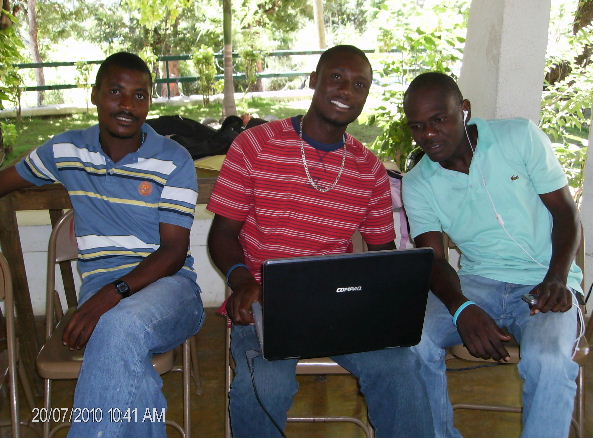

Laurore, on the left, with Brunel, who survived the accident, and Samuel, another CLM case manager. The photo was taken by Bethony Jean François.