Fonkoze’s Chemen Lavi Miyò, or Pathway to a Better Life, program is more than ten years old. And it’s been almost eight years since three of my Haitian colleagues and I spent a month in Bangladesh, learning the program from its creators at BRAC. That BRAC team would still recognize its work in all that we do, but the program has changed over the years as we’ve tinkered with it whenever we come upon what looks to be a way to make it stronger.

Over the last couple of years, the most important change has been the introduction of Village Savings and Loan Associations. (See: www.vsla.net.) CLM members attend weekly meetings, where they can buy from one to five shares of the association. The money they buy their shares with becomes capital that members of the association can borrow. They repay the loans with interest, so the capital grows. At the end of a year-long cycle, the association breaks the bank, distributing the capital among members in accordance with the number of shares they have purchased.

This morning I attended the final meeting of the year of a VSLA in Fon Desanm, a mountain community that lies a short hike upward from the main road that leads to Savanèt. The meeting took place in a small church., really just rough timber support posts covered by a tin roof and enclosed by walls of straw. There were a handful of narrow, wooden benches fixed into the packed dirt floor along the walls of the church and a table in the front that held the various things the meeting required.

About 35 CLM members had been buying shares for 50 gourds – about 80 cents – and together had purchased 160,150 gourds, or almost $2,600, worth over the course of the year. They were very excited about the payout. The return on their investment came in several forms. Members paid 2% interest per month on their loans and penalties for late payments. An additional fund, comprised of small weekly donations to be used to help any member who confronts an emergency, like a death in the family, was folded into the total. Taking it all together, the members accumulated more than 200,000 gourds that they need to separate among them. That’s about 25% more than the value of the shares they purchased.

The pay-off meeting actually took place in two sessions on consecutive days. On the first day, the association’s leadership, along with Martinière, the CLM case manager responsible for working with the Fon Desanm VSLA, counted and recounted all the shares that had been purchased. Each member has a small booklet with a star for every share she bought, and the association’s secretary keeps a notebook that lists all the share purchases by week. The two records are compared in the presence of the entire membership so that each member know what she and her fellow members have accomplished. Members repaid outstanding debts. Those who had debts they could not repay with cash repaid them giving back shares. There were five such women, and four of the five were able to clear their debt with about half of their investment or less.

Many of the women came early to the second day’s meeting, excited to find out how much money they had made and to receive the payout. There were only a few stragglers. It was a social occasion. The room was noisy, as the women chatted with one another. Martinière and the association’s leaders first counted all the cash. The total was 203,132 gourds. They subtracted a small sum that the group will need to restart the association for another one-year cycle. They’ll purchase new savings booklets and notebooks for record-keeping. They then divided what was left by the number of shares – 3,203 – to calculate the final share price, just under 63 gourds. They then called the women up, one at a time, to receive their payout, counting the cash out carefully in front of her. VSLAs need trust to function, but that trust is built on transparency.

Marie Yolène had purchased 107 shares over the course of the year. She had also taken out two loans, each for 3,000 gourds. The first helped her pay her children’s school fees, and the second she invested in farming. Paying them back was difficult, but she managed. She plans to use her payout for farming. She has agreed with a neighbor to rent a plot of farmland, and most of her money will pay that rent. But she will have enough left over to buy the seeds – beans, pigeon peas, and corn – that she’ll plant.

She liked the VSLA, and her explanation is simple. “I like it because if you need to borrow a little money, you have a place to find it.”

Rosana was very happy about the VSLA, too. She has big plans for her money. She and her husband have a house full of children, and 2017 was difficult because when it came time to plant, they didn’t have the resources to put in any crops. They had to figure out how to feed the kids for the year with whatever cash they could earn. He did day-labor when he could find it in their neighbors’ fields, and she managed a small commerce. Part of the VSLA’s value for her was that it gave her access to credit to restart her business each time she ran through her capital.

She took out loans three times, and says she never had trouble repaying them because she always used them to invest in her business, which would earn the revenue she needed for repayments as long as she could keep it afloat. “I made the money work, and as soon as I sold my merchandise, I would a payment.”

Like Marie Yolène, she likes the VSLA because it gives her a way to borrow money. “I can get a loan without leaving my community. I would have nowhere else to go. Rich people won’t lend you money.”

Not all the members of the VSLA are CLM members, or even women. The associations would be hard to build with CLM members alone. Too few are literate enough to do the record-keeping that the associations depend upon. Our solution is to bring members of the community’s village assistance committee into its VSLA as well. We organize these committees everywhere we work. They bring community leaders into the program as volunteers. Committee members bring an additional level of personal support and supervision to program members. Adding them to our VSLAs achieves two goals. On the one hand, they can provide literate staffing of critical positions. On the other, they establish an activity that CLM members and community leaders can share that is beneficial to both.

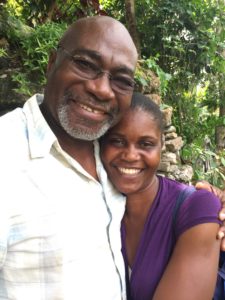

Daniel was the president of the assistance committee, and when Martinière told him about the VSLA, he decided to join it as well. “The women chose us as their leaders. We owe it to them to help out.”

He thinks that the VSLA really helped the poorer members of his community. “It really protects them by giving them a way to save and to borrow.” He saw the way some of them struggled to repay their loans, but was pleased that they somehow managed.

He also discovered that the VSLA was as useful to him as to its other members. “If you have 50 gourds lying around, you have a place to save it. You have easy access to loans. And the payout at the end of the year gives you something to hope for.”

He and one of his sons were the group’s two leading savers. They each bought 257 shares, which was about three times the average for the 38 members. And he’s anxious to get the next cycle started. “We’d start again tomorrow if we could.” He says that a lot of his neighbors are waiting to join as soon as the group is ready.

He and the group’s leaders were not the only men present at the meeting. Wisnel came in place of his wife, who still spends most of her time at home with their infant. He took over attendance at the meetings from her as her pregnancy started to make it hard for her to get around, and continued after she gave birth.

The couple’s experience in the VSLA was mixed. They took out one 3000-gourd loan, and it did not go well. Wisnel bought an avocado crop with the money, but a passing hurricane destroyed most of the crop while it was still on the tree, and the remainder rotted before it got to market when the truck he loaded it onto broke down on the long, bad road to the main highway. He and Modeline eventually had to reach into their savings and sell a goat to pay the debt.

But Wisnel is enthusiastic about the association anyway. They were about to buy 68 shares. “We worked hard, we saved, and we reaped our profit at the end of the year.” They plan to stay in the VSLA, and they’ll continue to borrow when the see a need or an opportunity. “We can’t be afraid of credit.”

Our program, and the communities we work in, still have a lot to learn about VSLAs. To this point, we find them functioning well when case managers take a strong hand in guiding them. Martinière’s leadership was evident throughout the meeting. They have run into trouble in places whether our case managers have decided to stay farther in the background. So we don’t yet know enough about how they function once the case manager leaves, after the CLM members graduate from our program. If we discover that the associations continue to need the program’s support to function well, we’ll need to choose between figuring out a way to provide it and letting the whole promising enterprise drop.