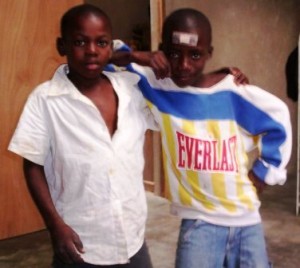

I’ve wanted very badly to share this picture of Yayi and Kaki ever since I took it a few weeks ago. They are from Upper Glo, the steeply sloping collection of small clusters of homes across the road from the wealthier cluster, or lakou, I live in.

The boys say that they are good friends. When I asked them what that means to them, they thought for a minute. Then Kaki, who’s on the right, said “Si m wè yon moun k ap bay Yayi yon kou, m ap tou antre.” That means that if he saw someone hitting Yayi he would jump right in. I have mixed feelings about the sentiment. I’m glad that they have each other to depend on, but I’m sorry that fighting was the first thing that popped into Kaki’s mind.

Fortunately, that’s not generally what they’re doing when I see them. I see them when they come down to the water source by the great mapou tree in front of our lakou. Fetching water is an important chore around where I live. Larger kids and adults will come to the source with five or seven-gallon buckets. Littler children come with gallon jugs. The smallest bring one jug, larger kids bring two or three, until they are big enough to carry a bucket instead.

As important as the chore is, it does not tend, for the children, to be very business-like. They’ll spend a good deal of time at the clearing just playing before they fill their jugs and head home. One of them might have a ball or a handful of marbles or some elastic bands. These are toys of choice. But an upripe grapefruit or a bundle of rags can substitute for a ball, and games like tag can be played without any equipment at all.

The other place I see them is in our lakou, where they will do small chores for various of the households. They might get a couple of pennies for their trouble, but they are more likely to just get a thank you and bite to eat, which seems fine with them. They might sweep or carry small loads of sand or rocks for construction, and though they can often be counted on to get their little tasks done, they are no more serious about their work here than they are under the mapou. Kaki in particular is quite the clown, and he seems to like nothing more than to make Yayi – and anyone else who is willing to look at him – laugh.

As I was thinking about this photo, I began asking myself why it seemed so important to share it. I wanted to figure out something that I could say about it. The fact that the boys are cute hardly seemed reason enough. After all, it doesn’t really seem to have anything to do with my work.

But the more I thought about Yayi and Kaki, the more I realized that their relationship to the various bits of work that they do sheds light on my relationship to mine.

Two facts have pushed me towards thinking about my relationship with my work these days. On one hand, I have a truly outstanding colleague at Shimer who has decided to take a leave of absence from teaching because, at least in part, he would like to be able to make his non-working life more interesting. When I say that the person I’m thinking of is “outstanding,” I mean the word literally. My colleagues at Shimer are all very good, but this one stands out for his thoughtfulness, his diligence, and his openness to learning. He’s a model. On the other hand, I’ve been in conversation recently with a group in the town where I grew up that is willing to have me come and speak to them about my life in Haiti. That group seems at least as interested in the life I live among my Haitian friends and colleagues as it is in the particular educational work that I came to do.

The latter point was, at first, a little surprising to me. I think of myself as a classroom teacher. It’s true that a lot of my activity in Haiti has more to do with helping other teachers establish conditions within which they can work in a classroom – the collaboration with Fonkoze is only the most extreme example of this – than it has to do with any direct contact between me and students. Even so, helping shape classrooms is the heart of what I think I do.

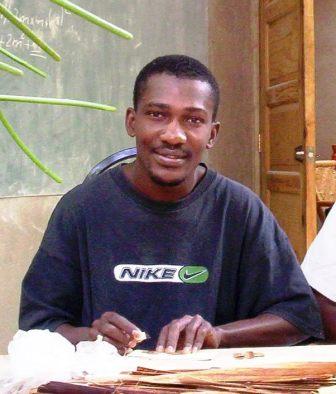

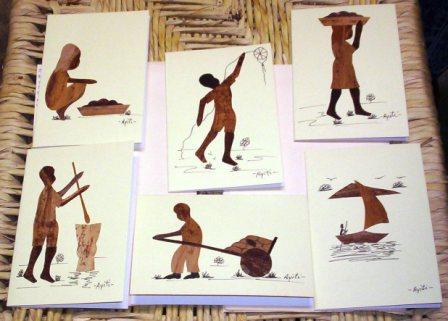

At the same time, I’ve always taken the name that Frémy and I gave our project quite seriously. We call it the Apprenticeship in Alternative Education, and though “apprenticeship” is slightly misleading as a translation of the Creole word, “aprantisaj,” that Frémy initially chose, it succeeds nonetheless in putting emphasis in the right place. I am in Haiti, first and foremost, as a learner. It is because I am learning that I think I can help others do the same.

But when I think of what I am learner here and how and in what situations I am learning, then the line between what I might, according to some conventions, identify as my work and what I would identify as my private life begins to blur. It loses its meaning. Because surely I’m as much of a learner in conversations with people like Yayi and Keki as I am when I’m trying to figure out an essay by Piaget with colleagues at the Matenwa Community Learning Center or when I’m helping to work out a budget for educational programs with colleagues at Fonkoze.

And I have the good fortune to be able to make the same claim the other way around: Just as I can see my everyday life as part of my work as a learner, I can also see what might conventionally be called my job as a part of my everyday life. I do not leave my home life to go to work, nor do I leave work to go home. It is one life.

Concepts like “time off” and “overtime” and “vacation” only make sense if you are selling your time to someone who’s assignng you to do something you’d rather not do. Make no mistake: I know perfectly well that there are lots of reasons why someone might choose to or might have to do this. But, at least right now, it’s not something I have to do.

My work in Haiti has a lot in common with the trips to the water source that Yayi and Kaki make. It’s very had to distinguish it from play, and I can’t think of any reason that I should.