Cenel Joseph is a single man. He lives in Tomond, a few minutes north of the downtown area along the national road to Ench and beyond.

As a young boy, he was helping his mother bring a load of mangoes to Pòtoprens in one of the many large trucks that worked the route. Back then, the road was unpaved, and the last hill separating the Central Plateau from the metropolitan area around Pòtoprens, Mòn Kabrit, was notoriously dangerous. The truck that he and his mother were in lost its brakes heading down the final slope, and she was killed in the accident that ensued, as was the boy’s uncle. He was badly hurt. He spent seven months in a hospital bed, and he lost his foot. He’s been moving around ever since on a single foot and two crutches.

Losing his mother changed his life. She was the one who really cared for him. Though he had been a poor student, she always made sure he went to school, but he dropped out after her death. He would farm a small plot of land, but he struggled in the muddy soil during planting and harvest seasons. His crutches would get caught in the deep mud, making it hard to get around. He had friends who would give him small amounts of cash, but often he would go hungry. “Sometimes I would just go off into my field to cry.”

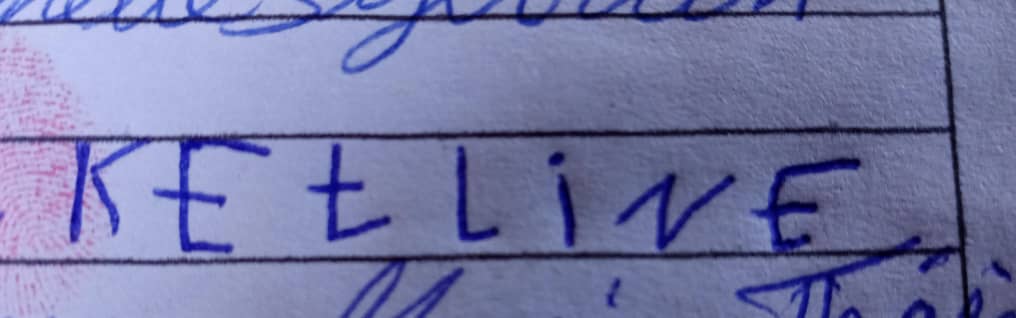

Cenel joined the CLM program in early 2020. The CLM team had been going through its selection process in his neighborhood. He did not initially show up on the team’s lists because those are made up of the households that each community identifies as belonging to it. Cenel was not a household. He was living in his father’s home. But the team’s supervisor came across him and struck up a conversation. As he came to understand how difficult Cenel’s life was, he assigned a staff member to collect initial data about him, then he verified the data and invited him to join the program. Cenel was excited. “I would just sit by myself by the side of the road, waiting for what might come. When they asked me whether I wanted to join the program, I thought it was a gift from heaven.”

He chose goats and a pig as his two enterprises, and his results were mixed. His first pig was stolen, and when Fonkoze helped him replace it, the second pig died.

His goats fared much better. The program gave him two, and he has grown that investment by managing the animals carefully. He now has seven. He plans to sell some of them so that he can buy a cow. He explains that cows involve less risk because you can let them graze farther from home. Goats get into peoples gardens. They lead to conflict. Already he is struggling to care for as many goats as he has, and he has started to assign some to young neighbors. Each cares for one and then gets some of the goat’s offspring as payment. It takes some of the pressure off Cenel and helps young people get started in life. This latter point also helps him manage some of the jealousy neighbors might feel at his success.

That success, however, has much more to do with the business he’s established than with his livestock. When he and his case manager began to talk about home repair, he insisted he didn’t really want a house. He wanted to build a small, one-room building at the side of the road that he could use as a little convenience store. He would put a bed inside and sleep there, too, but he would mainly use it to sell basic groceries.

Because it was so small, he was able to finish it quickly. He took out a loan for 10,000 gourds from the savings and loan association that CLM set up for him and the other members who live near him, and he bought his first merchandise. He used half the money to buy food basics, like rice, oil, and sugar, and the other half to buy hygiene products, like soap and shampoo. He made the effort to travel to Ench, the Central Plateau’s largest city, to purchase what he needed. The prices there are slightly lower than Tomond because there’s more whole business going on.

His store business took off. He returned to Ench once each week, buying more and more products each time. By settling on a small number of wholesalers, he enabled them to see him often and to gain a sense of his reliability, and soon they were allowing him to buy for more than the cash he had on hand, owing them a running balance, so that he could expand his business even more.

His earnings allowed him to continue to save in his savings and loans association, but he did more than that, too. He join a sòl, a Haitian savings club in which members make weekly contributions and then one receives the whole pot each week.

And when he decided that the association and the sòl offered too little opportunity for savings, he himself established another device for himself and 13 of his neighbors. It is called a “sabotay.” The fourteen participants each contribute 250 gourds every day, and each day someone takes the pot. And he has uses for each type of savings.

He repaid his loan from the association, and he took out another, larger one. The second one was for for 15,000 gourds, and he combined that money with money from his sòl to buy a freezer for his shop. He now sells cold drinks alongside his groceries. “I keep the money from the groceries and the money from the drinks in two separate buckets so I know what I am getting from each.”

When his association completed its first one-year cycle, he used the money to buy an additional goat. “The goats are important for my business. If I have a loss, I can sell a goat and the business will keep going.” The next time his turn comes around in his sòl, he plans to use the money to buy his cow, selling as many goats as he needs to add to the money. He has a plan for his sabotay as well. He will use that money to buy cinder blocks. He wants to tear down the wooden walls of his house and replace them with blocks and cement.

What is most striking about Cenel’s success is that all of the thinking behind it came from him. He has shown since joining the program unusual creativity and initiative. Each new idea was his own. He would suggest it to his case manager to hear her advice, but he is happy to tell you that the ideas were his. This makes you wonder why he couldn’t get started until CLM came along.

Cenel’s answer has a couple of elements. On one hand, he is quick to explain that before he joined CLM he didn’t have the vision. Even as he entered the program, he wasn’t able to imagine himself running a business. That’s why he chose two forms of livestock as his initial enterprises even though the program would have been happy to provide merchandise for small commerce in place of the pig. “You attend the workshops and you hear what other people are doing. It makes you think.”

He also talks about how he learned to manage money. He was always getting 50 or 100 gourds at a time from friends or neighbors who felt bad for him, but he would spend all of it on food right away. “You learn that even if you only have 100 gourds, you should eat only 75 and save 25. Little-by-little you can build up what you need.”

And he comes back to the livestock as well. Before CLM he had none. He was afraid of business because any loss would be irreparable. Having goats as additional assets as insurance against losses helped him feel the confidence he needed to start investing.