Orana Louis lives in Bay Tourib with her husband Sòn and their six kids. Few of her neighbors know her by that name. They have called her Jaklin ever since she moved to the area from Mannwa with her mother Mirana. Her father had passed away, and her mother came to Bay Tourib to move in with another man. Jaklin and Mirana both graduated from the CLM program in March 2013, and Jaklin’s time in our program was especially transformative.

When we first met her and her husband, they were struggling to get by with farming. They had no assets to speak of except the land that belonged to Sòn’s family, but they didn’t have the resources to invest in seeds. They depended completely on seeds they would borrow from a local peasant organization. They didn’t have a home of their own. They were living in a small house that belonged to one of Sòn ‘s brothers.

Their main source of local income was agricultural day labor. Jaklin and Sòn would do work when they could find it in their neighbor’s fields. Sòn often went to the Dominican Republic for months at a time, and when he returned to Haiti, he’d try to come with some extra money. Jaklin would use it to buy plastic sandals in Tomond, which she’d sell in the rural markets around Bay Tourib. Each time she would restart her business it would work for a while, but eventually collapse. Often the problem was pregnancy. She couldn’t run her business because she was busy nursing a child. And whenever Sòn was away, she’d have to dip into her capital to manage her household. The family was hungry most of the time.

Things began to change when she joined the CLM program. She chose small commerce as one of her two enterprises, and so received an infusion of capital into her business as a transfer that she didn’t need to repay. She also received coaching, which helped her keep better track of her business.

She decided to expand the same business she had been trying to establish for years. She continued to buy sandals at the market in Tomond, the nearest town, and lug them for sale to the remoter markets in Koray, Regalis, and Zabriko. With her older children now big enough to watch the younger ones sometimes, and Sòn around all the time to give her a hand, her business started to take off. The couple saved money from her regular cash stipend to invest in their own farming, and they had a couple of good harvests. These harvests, in turn, enabled them to invest more in the sandal business and, more importantly, to buy a horse and then a mule to carry merchandise.

Between the added capital and the pack animals, Jaklin was able to expand her business dramatically. She was soon sending Sòn to buy her merchandise in Port au Prince, where the variety was greater and the prices were lower. And their growing business made further investments possible: farmland, a grain storage depot, and better schools for their kids. They built a house of their own on the family land they had been living on, and they bought a large garden from Sòn’s mother.

And their progress continued despite setbacks. When Sòn lost most of the capital in the sandal business during one of his trips to Port au Prince, they shook off the loss and kept moving forward.

In 2015, Jaklin became pregnant again. And this last pregnancy was especially difficult. Her labor went poorly, and she had to be rushed down to the Partners in Health hospital in Hinche. The doctors’ care there was free of charge, but the hospital is badly undersupplied with medications and other supplies, so Jaklin and Sòn had to spend the capital in the sandal business to pay for what she needed. She eventually required a C-section. She gave birth to a healthy boy, and asked the attending doctors to make sure that Rivalda was her last child.

When she got back to Bay Tourib, she was stuck nursing another baby, but the baby was healthy and she gradually regained her own health as well. Her sandal business, however, had been reduced to nothing. When she was ready to start getting around again, she had no merchandise and too little capital to buy any.

So she and Sòn made a new plan. Instead of the larger investment that the sandal business needed, she decided to go to the rural markets every week and buy up all the beans she could afford. Each week, she would take a load down to Tomond. She wouldn’t make a lot, but the income would be reliable. The standard rural unit of measure in Haiti is a large coffee can, a “mamit”, and Jaklin would be sure to make 15 to 20 gourds for each mamit she’d sell. “The sandals take more money,” she explains. “But once we harvest our beans in the fall, we’ll have the money to buy sandals again.”

So she and Sòn have a plan and the confidence to know they can manage. They are not at all a wealthy pair, but they are smart and resilient, so their future is bright.

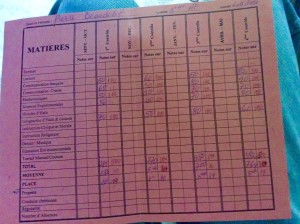

Jacklin with her five younger kids