Rose André. lives in Hat, a farming community between the Artibonit River and the road that runs east out of Laskawobas towards Beladè and the Dominican Republic. She lives in the same lakou, or yard, that she was born in, sharing her house with her two younger children and a grandchild. Her brother and sister-in-law live with their children in a small house less than 20 feet away. Rose André’s oldest child lives and works in the DR, and her second child lives with the girl’s father.

For the past three years, she has been sharing the house with Renold. They couple does not have children together, but Renold has no other children and Rose André likes the way he treats hers. “”He’s nice to them and he helps them.”

Before she joined CLM, she and her family were getting by mainly through farming, planting manioc and sweet potatoes on rented land and planting plantains right around their house. Hat is fertile and wet, so folks with access to farmland can profit, and that means that she and Renold could usually find farm work, even just day-labor, to earn a measure of cash when they needed it. She herself mentions their need to buy beans.

She had tried to start a business. She borrowed money from a community association and bought cheap housewares, like buckets, washbasins, and other plastic items, at the international market in Elias Piña, inside the Dominican border. She would bring her merchandise to various local markets — Mibalè, Kolonbyè, Laskawobas, Kwafè, and Mache Kana — and hike around calling out and selling her wares. But her household expenses were too much for the business to support, and the money she invested slipped through her hands. “I didn’t have any of my own money in it. I had to pay back some every month. And also pay for the kids’ school and feed them every day. The money disappeared.”

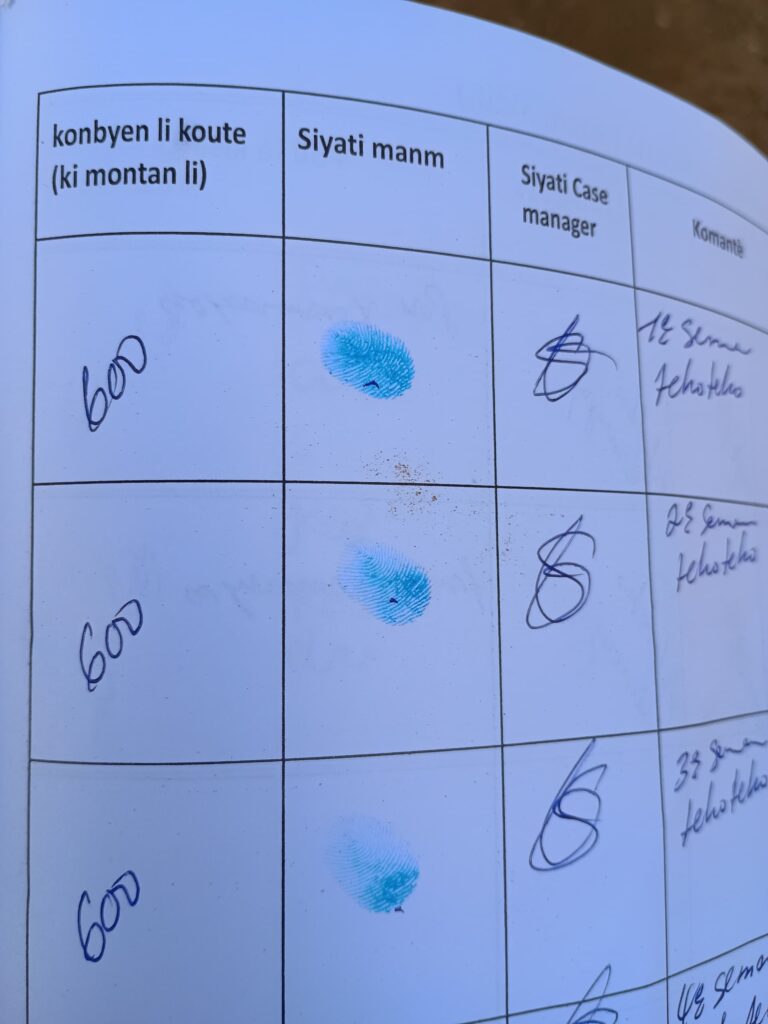

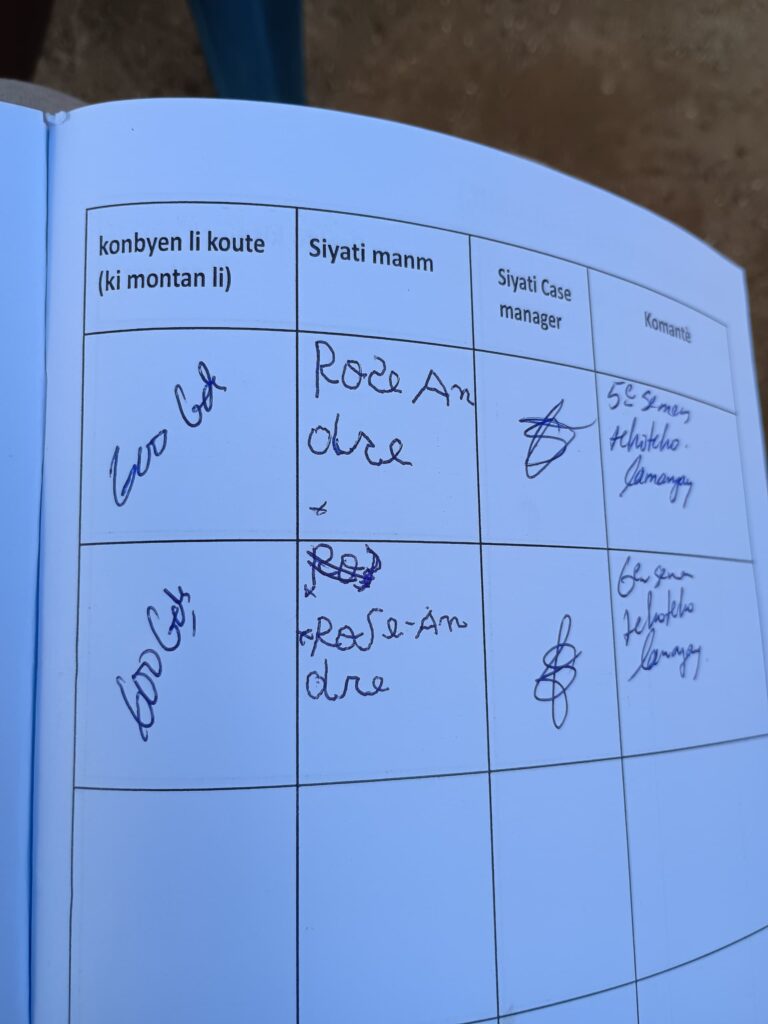

Since she joined CLM, Rose André has been working hard to learn to sign her name. The photos below are from Rose André’s CLM information book, where she signs for her 600-gourd weekly stipend. On the left, she was signing with a thumb print, but now she writes her whole name.

And she has also started to make a plan. The team has begun transferring business assets to members of her cohort, and Rose André knows what she would like to do when she receives hers. She wants to start by buying a large female goat. “They say I should buy two smaller ones, but if they are small they can take time to have their first kids. A big female can begin to produce right away.” She explains that she will receive 23,000 gourds to spend on assets, and she figures she can get the sort of goat she’d like for 10,000 gourds.

She will use the rest of the money to go back into business selling housewares. “It will hold up this time because I will have mine own money in it. I can borrow money to make the business larger, but most of the money I won’t have to pay back.”

She has a clear way of saying how she’d like her life to change as she moves forward in the program. “I want to be able to feed us with my own money. I don’t want to have to ask the merchants to sell me food on credit anymore.”

Wideline is excited to be part of the CLM program. “It is a family that’s formed. If I have a problem, I can call Makenson. He’s there for me.” Makenson is Wideline’s case manager, and she likes his weekly visits.

She lives in Hat now, but she comes from Flande, an area west of downtown Laskawobas on the road to Mibalè. “When you’re the woman, you go where your husband takes you.” But she and her partner have neither farm land nor their own home. Right now, they rent the place where they live for 10,000 a year. That’s about $75, which might seem like very little for a twelve-month rental, but it was a lot for her and her partner, Roro, to assemble.

She used to support her family with a small grocery business that she ran out of her home. She sold basic foods, like rice. But keeping her kids fed and paying for their school ate away at her capital until she had no business left at all. She also used to plant vegetables, like okra, that she could take to the market for sale, but she lost access to the land she was farming. After that, she had to support her family with whatever she could earn working in her neighbors’ fields.

Like Rose André, she has been thinking about what she will do with the investment capital the CLM program will provide, and like Rose André she wants to invest both in goats and in commerce. She plans to use some of the money to get her food business going again, but she also wants to get into regular market trading. That means going to the market with cash to buy and then sell whatever seems profitable.

But she’s most excited about what a goat can do for her. “If I have one goat, and can eventually have two. Keeping goats can help me to have a place to live, to pay for school, and to handle my problems.”