Claudette and Franckel

When Claudette joined the CLM program, she and her husband Franckel had very little. They were living with five children in a single room they rented near the Labasti market, which sits along the main road between Port au Prince and Mirebalais. Four of the children were theirs, and one belonged to Claudette’s brother Manny, who lived nearby. She had been living with her aunt and uncle for years.

The couple struggled to send both their oldest girl and Manny’s girl to school. To pay the tuition and other expenses Franckel would turned wood that belonged to neighbors into charcoal and take half the revenue. He also did day labor to keep the family fed, earning less than $1 a day in their neighbors’ fields. Occasionally, he’d getting a job on a team milling sugarcane for a few days. That would be a windfall. Claudette didn’t contribute to the household’s income. With the couple’s twin toddler girls and the infant boy who followed them, her hands were more than full.

They chose goats and a pig, and got to work, taking good care of their livestock. They couldn’t afford to buy land to build a home on, so they talked to Franckel’s brother. He gave them a small plot downhill from a larger one that he claimed from their half-siblings. The brother is a difficult man, a bully. That’s what enabled him to claim the land from their siblings. It didn’t really belong to the half of their family that he and Franckel were part of. But the brother presented the only way that Franckel and Claudette saw of establishing their own home, so they dealt with him as best they could. To make things worse, the man was jealous of their participation in CLM. He and his wife had been too wealthy to qualify. So Franckel and Claudette had a lot to do to manage the relationship.

Things weren’t easy, and their frustration built as their livestock failed to multiply. By six months into the program, their pig was growing, and it would soon have piglets. But the piglets all died. Even at twelve months, their two goats were still just two goats. So the couple prepared to make a difficult decision. Their baby was no longer breast feeding, so Claudette would leave their area to seek work as a maid in Port au Prince. The work would be poorly paid, but it would be regular income. Franckel would have to manage things at home with the help of their older girl and their niece.

But something got in the way. Claudette’s brother Manny became dangerously sick. He had severe constipation and accompanying stomachaches. Franckel’s brother was close to a Vodoun practitioner who made money as a healer, and he convinced the couple to let his friend take care of Manny. Claudette could only watch as Manny’s condition deteriorated.

One rainy afternoon, however, seeing Manny in agony, Claudette made a courageous decision. She took him from the healer’s compound, put him on a motorcycle taxi in the midst of a tropical downpour, and rushed him to the Partners in Health University Hospital in Mirebalais. Doctors performed emergency surgery to remove the blocked section of his intestines, and so saved his life.

The cause of his trouble was extra pulmonary TB, and Manny would need at least six months of treatment after he left the hospital, so the couple built a small shack next to their own, where they could keep Manny with them while protecting the children from possible infection. He became a full part of the household. They helped him get to his follow-up appointments, and cared for him as he recovered. As he gained strength, he began to help with housework. He had long been a hard-working farmer, but initially he could just manage the smaller chores. He was anxious, however, to do whatever he could.

Meanwhile, the couple’s livelihood was undergoing a transformation. They found a landowner who was willing to let them work a small plot as sharecroppers. They would do all the work, and keep half of any income. Franckel first cultivated it for the charcoal he could make from the wood growing on it, and then invested the money from charcoal sales into planting a crop of beans.

They also found someone willing to sell them 2000 gourds worth of sugarcane on credit. Claudette explains the opportunity: “Making money from cane is a lot of work. Some people would just as soon take the easy money and be done with it. But Franckel’s not like that. If he sees a way to make an extra 50 gourds, he’s always willing to make the effort.” They used the income from that sale to buy another load of cane. “Franckel found someone who had a cane field they had already harvested. But he thought it looked like it had a lot of cane still in it, small plants that would grow if they had a little more time. He bought the harvest for 5000 gourds, and eventually sold 15,000 gourds worth of cane.”

But even as they were beginning to find a path towards financial success, their lives grew more difficult socially. Franckel’s brother was angry that they had turned their back on his friend, the healer. And his jealousy only intensified as he watched his brother’s lot improve. So he decided to run Franckel and Claudette off the land he had provided for them.

Fortunately, it was at about this time that their first bean harvest came in, and it was a good one. They sold it off and made good use of the profits. They bought a horse, and made a down payment on a small plot of land that they could build a house on. They threw up a three-room shack. They wanted Manny to have his own room. It wasn’t much, but it put a tin roof over their heads and it was theirs. They had to sell off their goats to get the house built, however, so they were left with farming as their only economic activity. And with Manny and five children on their hands, things were very tight.

When Claudette graduated from the program, the couple had their horse and a couple of chickens, but all their other money was in the fields. And Claudette was pregnant with what would be their last child. As Franckel explained at the time, “We know that our family is already large, but we want one more, and we are sure that we can support all our kids.”

Their success with sugarcane is what changed their lives. Claudette and Franckel began to buy all the cane they could, and would rent local mills to turn it into molasses. They’d then sell the molasses to rum distilleries. With each new purchase, they had more to invest. Soon, they were farming sugarcane, too, paying five-year leases on plots of land. Eventually, they had over three hectares under cultivation and a sugar mill of their own.

And as they rolled over the capital that they invested in sugarcane, they invested in the quality of their lives as well. They poured concrete over the packed dirt floor of their home, and repaired and painted the planking that made up its walls. They re-did its small porch with cinderblocks and cement. They bought the plot in front of the house to plant a garden. Their three younger children joined the two older girls in school.

Many CLM graduates are successful, but Claudette and Franckel know that few have been as successful as they have. “Some graduates are willing just to keep the things they have,” Claudette explains, “but we always are trying new opportunities.”

Each has an explanation for their success, and their explanations converge. Each credits the other. Franckel says that Claudette has two qualities that really help them. “She works hard with whatever we have, and she never complains when we have nothing.” Ever since she weaned their youngest child, he’s made sure that she always has some capital to manage a small commerce. She buys loads of whatever produce is in season, and sells it in local markets. “Since she manages the house with her business, I can focus on bigger things.” For Claudette, it’s Franckel’s willingness to work hard wherever he sees an opportunity. “He doesn’t worry about doing things the easy way. When you are in a difficult situation, if you see a path out of it, you have to be willing to take it.” For both of them, it starts with their willingness to discuss all their decisions and make them together.

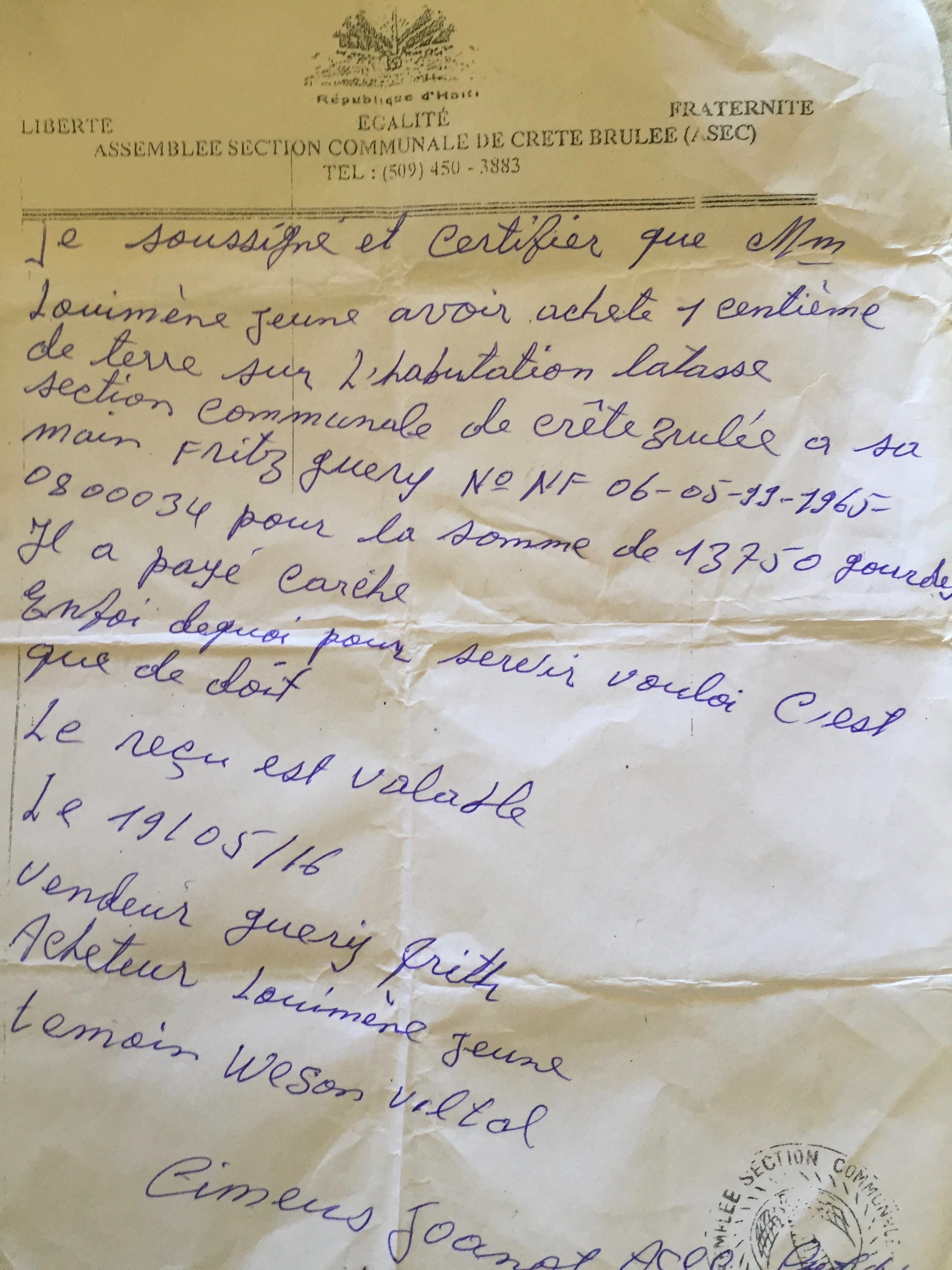

And they seem well on their way to continued success. With money from the sale of their sugar mill and 100,000 gourds they borrowed from a local credit union, they made a down payment on another hectare of land. This one they will own. Their next cane harvest should enable them to complete the purchase. Here, there is a small disagreement between them. Franckel wants to build a new, larger home on the new plot. Claudette would rather stay where she is and use the new land for farming. “We’ll have to discuss it,” she says.

And Claudette is making progress in another sense. This year, she found an afternoon school program for adults at her church and she entered the first grade. “I go to meetings and there are folks old enough to be my parents who can read and write, and I can’t. It’s embarrassing.” She had never been to school before.