I’ve written about Louimène before. (See: Louimène.) Her paths into and through the CLM program were both unusual. She initially missed out on the program, not because the CLM team missed her when they passed through her neighborhood in Labasti, nor because they mistakenly thought that she didn’t qualify, but because she temporarily moved from her own home to her mother’s between the time she was selected for CLM and the time she was slated to begin. The older woman was sick, and Louimène had gone back to Bouli to care for her.

It was unfortunate because Louimène, her partner Lucner, and their two boys really needed CLM. They were living in a straw tent-like structure on land they neither owned nor rented. Someone who used Lucner to help him do his farming let them use a corner of a field to live on. They had been driven away from Lucner’s family’s land by some of his relatives. They could hardly have been poorer.

They got a second chance when another CLM member abandoned the program almost nine months after it started. That left Louimène, Lucner, and their case manager half the usual time to work together, but thanks to the couple’s willingness to work especially hard, she graduated nonetheless.

They didn’t receive the full complement of livestock that members normally receive, only what could be recuperated from the woman Louimène replaced. But they took good care of their animals, and they flourished. Lucner took any work he could find in neighbors’ fields, and Louimène started a small business. She invested 1000 gourds she received from the program into a small commerce, buying spaghetti and canned milk. She carried it on her head five miles into Mirebalais, selling it on the way. She’d restock when she got to town.

They continued to struggle some after Louimène graduated. Lucner went through a long period of bad health. He was weak. He couldn’t work the way he was used to working. It turned out to be H. Pylori, a bacterial infection that can be hard to cure. Louimène went through two pregnancies, and their small family of four became a family of six.

Worst of all, the man who had given them land to squat on began to resent their presence. He made things difficult for them, showing them that he didn’t want them there any more. Initially, they had to put up with his humiliations because they had no place to go, but eventually they found a very small plot of land they could buy by selling the cow they had bought at the end of their experience with CLM. They took the tin roofing off their house and built a new shack on their own land. They also went to the trouble of installing a latrine.

Things improved some for the couple and their children after they moved. Lucner returned to health, and though the couple had no farmland of their own to work, they were able to rent a plot. Lucner farmed that plot and worked a second as a sharecropper. Until last year, they continued to count on his harvests, but the prolonged drought that struck Haiti last year ended up destroying their fall crops. It then extended far enough into this year’s customary planting season that Lucner’s been reluctant to invest much into new crops.

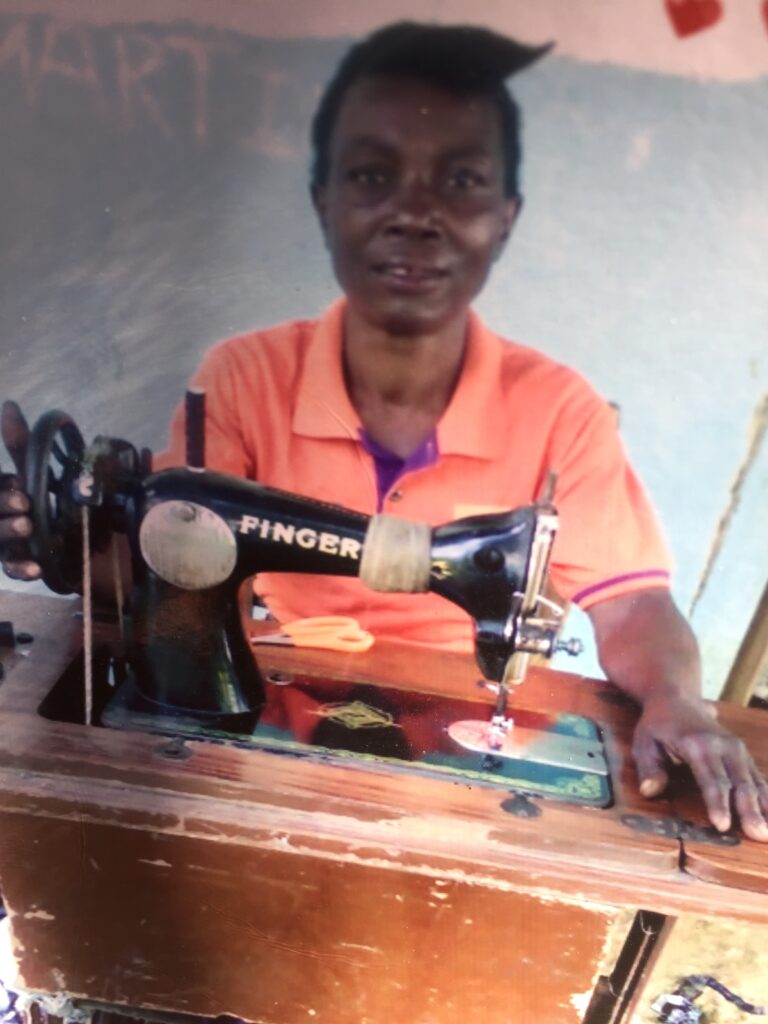

Louimène continues to earn money through small commerce, however. She sells basic groceries. She’s currently the principal earner, bringing in enough to feed the family and make weekly contributions to her savings club, or “sòl,” Every week, members of the sòl make a set contribution, and one of them receives the whole pot. When it’s Louimène’s turn to receive the pot, she usually invests it right into her business. So her business grows and shrinks cyclically as the date of her receipt of the pot is nearer or farther away. At times, it is nothing more than garlic and bouillon cubes. At other times, she sells rice, oil, and other staples as well. Its value can shrink to as little as 1500 or 2000 gourds, but it can grow to 10,000 gourds as well.

But though their income has grown only slowly since Louimène graduated, their lives have changed in important ways. Despite their struggles, they recently bought a small pig, their first investment in new livestock in a couple of years.

And Louimène is quick to talk about another, more important change. She and Lucner married in December. “We got married, and started going to church.” They can’t attend services during the coronavirus crisis, but they can pray with their fellow congregants. “I visit neighbors’ homes every morning so that we can pray with them.” Louimène no longer carries her merchandise all the way into Mibalè on her head. On Thursdays, she sets up her business at the market. On other days, she sells right out of her home.

Between her business and Lucner’s farm income, they’ve also managed to create a different sort of home. They tore down the walls of their shack, which had made of thin sticks that were woven and then covered with mud. In their place, they covered the two sides of their home and its back with palm-wood planks, which they painted a creamy orange. They built a new front wall of stone masonry. It is much more solid and attractive than the house it replaced. They also enclosed what had been a covered porch-like area in the front, so the inside of the house is about a third larger.

And they continue to make plans. The children lost out on school this year, but they are already focused on sending the two boys in the fall. They aren’t sure about their third child, the older girl. The baby isn’t ready. Louimène plans to continue her business, and Lucner is thinking of starting in commerce, too. He has experience in it from his years living in Pòtoprens, and he thinks it might be a safer investment than farming, especially for someone without their own farmland.