Jean Manie is a CLM member who lives in Chimowo. Working with CLM members is always challenging, but Jean Manie has presented Alancia, her case manager, with real difficulties. I’ve written about her before. (See Jean Manie.)

Many of the special challenges she presents grow from her upbringing as a restavèk, a child living in domestic servitude in someone’s home. She spent her earliest years at her aunt’s house. Her own parents died when she was an infant. But by the time she was a very young girl, she had moved in with her married cousin Irma and Irma’s husband Moussa and was doing all sorts of unpaid household labor — from cleaning and laundry to farm work and babysitting — to earn her daily bread.

She never went to school of any sort. But what’s worse, she never was encouraged to see herself as capable of anything. Especially decision-making. Jean Manie was never encouraged to imagine herself doing anything but other people’s hard work.

The first big change that CLM was able to bring to her life was when her first case manager, Sandra, convinced Moussa to send for Jean Manie’s eight-year-old boy, Patrick. As a toddler, Patrick had been shipped off to the home of Jean Manie’s aunt. Moussa had said that he couldn’t afford to feed both him and his mother. Jean Manie would visit him occasionally, when she “really missed him,” by hiking across Boukankare from Moussa’s home in Chimowo to the aunt’s on Mòn Dega.

But that was really only a start, because it quickly became clear that Jean Manie would never make any progress until we could help her leave Moussa’s home. Any investment CLM would make in her would be sabotaged by Moussa’s insistence that his work be her priority. He allowed her to accept the young goats that we gave her, but wanted us to allow him to simply add hers to his. When Alancia, her second case manager, wouldn’t agree, Jean Manie’s goats quickly grew ill. She simply had no time to take care of them. And that wasn’t the worst. The healthy pig we gave her gave birth to piglets — that’s a lot of value — but its death followed shortly after theirs because Moussa would not give her the time she needed to keep them fed.

When Moussa insisted that she should build her CLM house on his land, Alancia put her foot down. A short series of events led to a usefully disastrous deterioration in the relation between Jean Manie and Moussa and his wife. They threw her and Patrick out.

She and Patrick now live in their own small, two-room house near Chimowo. They’ve been there since November and could hardly be happier. Patrick had been a picture of oppression when he lived with Moussa. If he spoke at all, it was in barely audible tones. He wouldn’t look anywhere near you, keeping his sad eyes focused on the earth in front of him. When I spoke to him in November, he said that “they” could kill him. He would not return to Moussa’s house. Not even just to run an errand. Eerie words from such a little boy.

Now he’s a picture of happy boyhood. He runs to Alancia, calling to her, when he sees her approach his mother’s house each week. He climbs on my motorcycle, pretending to be its driver. That is: He now does just the sorts of things that happy boys do. As our program’s director, Gauthier, puts it: “He’s free.”

One key step in their progress came in a manner we could not have predicted. In talking with Claude, the secretary of the Village Assistance Committee that we helped establish near Chimowo, Alancia discovered that he had long heard rumors that he was Patrick’s dad. He admitted that he had relations with Jean Manie on one occasion, though they had never dated. In further conversation, he admitted that Patrick’s resemblance to him was striking. So he talked with his wife, and decided to accept Patrick as his son. Though Patrick would remain with Jean Manie, Claude would make a commitment to helping them out. He’s the one, then, who gave her the land she needed to build her little house, and helped significantly with its construction. He took her goats for her and nursed them back to health, and he now cares for her small cow.

Things started looking up for Jean Manie. Patrick was happy and in school. She and he were in a nice, though small and basic, new home. And her asset base — her livestock — was stable and ready to grow: two now-healthy goats and a cow that she bought with sales from the meat of the dead pig and her savings.

The key would be if she could develop a regular income stream to ensure household expenses, but this problem seemed solved, too. She entered in to relations with a young man. He worked at a local sugarcane mill, and would bring her logs of the unrefined brown sugar that rural Haitians use to make, among other things, their morning coffee. She’d sell them and use the money to put food in the house. He also asked her to look after his pregnant pig. Normally, that would earn her a share of its young.

But the relationship soon deteriorated. Jean Manie went to the hospital because she wasn’t feeling well — an encouraging sign of her sense of responsibility — and was told she had a minor infection. The nurse told her said that she should abstain from sexual relations for about ten days. When she explained that to her new boyfriend, he assumed that she was making an excuse to get rid of him and grew angry. He took his pig, his other belongings, and some things that belonged to her, and left the house. At the Village Assistance Committee meeting shortly afterwards, members decided to talk to him to convince him to return the things he took, but Jean Manie has decided that the relationship is over.

So she is going to have to establish a regular micro business now. She and Alancia have decided she’ll sell kerosene in the local markets. She should be able to make enough money to keep herself and Patrick fed if Claude occasionally contributes as well. And he says he will.

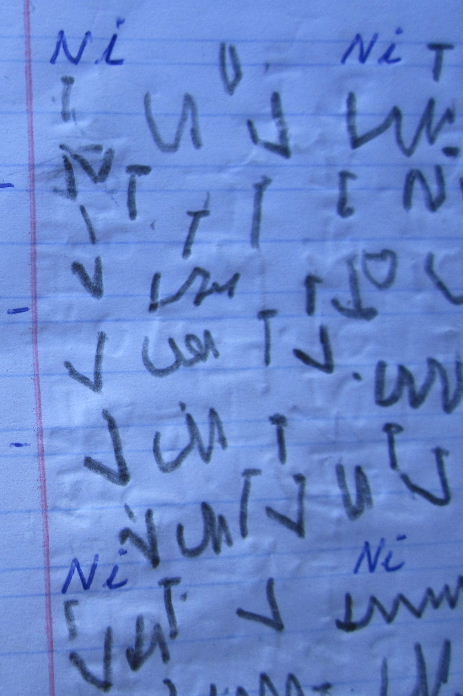

The problem is, that she can’t do any but the very simplest math. She can calculate change for numbers ten or less, but when Alancia asked her how many Haitian dollars she would give a customer who purchased three dollars of kerosene with a twenty-dollar bill, she said, “One hundred fourteen-ten.” That’s “sankatòzdi” gourds, and it makes no more sense in Creole than in English.

But she needs to start her business, so she’ll start it small. Alancia will work with her on making change. Jean Manie and Alancia got another CLM member, Tona, to agree that they could set up their businesses next to each other. Tona will keep an eye on Jean Manie as she makes change.

So Jean Manie is set to move forward again, and it’s none too soon. She scheduled to graduate from the program in June or July. She needs to be running a small business that she can count on by then.

Research and photos for this piece by Ellien Delice.

Research and photos for this piece by Ellien Delice.