Getting to and from Chito is challenging, at least during the rainy season. Chito is a small community in Kolonbyè, the westernmost section of Savanette. It’s the section where our team is looking for qualified families for a new cohort of CLM.

Even just getting to Kafou Debriga, the point from which we set off for Kolonbyè and Chito, requires you to cross a river a couple of feet deep. I’m told that, during the dry season, one can get all the way to Kolonbyè on motorcycle, but we left ours in Kafou Debriga because the main river, the Fer à Cheval, looked dangerous. It was challenging enough to ford it on foot. The quickly rushing water was well over knee-high. Trying on a motorcycle would have been needlessly risky.

When we got across the river, we split into two teams. Most of us went to the left, towards the area around the Kolonbyè market. Wilson and I went with a couple of case managers to the right, towards Chito. The area had about 23 families whom our case managers had already recommended for inclusion in the program. Wilson and I would be responsible for making the final determinations.

Chito is a fertile, green area that rises from the river towards a mountain to its south. It’s mango season, and there were mangos, and children eating mangos, everywhere, but also trees of many other kinds. Chito shows little sign of the ravages that charcoal production is responsible for in most of rural Haiti.

And its homes seem more-or-less evenly sprinkled throughout the trees in clusters of two, three, or four. They were of various sorts, all if them small – just one to four rooms – but some had decent tin roofs and well-made cinderblock walls. The ones we were visiting though were mostly of a kind: one or two rooms enclosed by palm planks and covered by tach, the thick, fibrous sheets taken from a palm tree’s seedpods.

The first woman I met was Nadia, a 22-year-old mother. She had been sent to Port au Prince as a young girl because her mother could not support her, and there she lived as a domestic servant in another family’s home. She eventually ran away from that family and found a paying job as a maid.

When she became pregnant, she thought about her options, but she decided to move back in with her mother. By then, her mother was partially paralyzed, unable to care for herself, and Nadia thought she’d have a friendly roof over her head and an opportunity to help her childless older sister care for their mom.

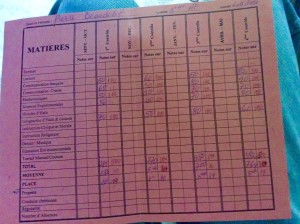

Nadia was clearly without means. On the section of her poverty scorecard that describes her assets, she scored a perfect zero: no livestock or productive assets of any sort. She scored another zero in the section measuring income. Her total score was less than one-third of an average result, and most of her score came from points she earned by having only one child and having access to good drinking water.

But despite her dire and obvious poverty, it wasn’t immediately clear whether to accept Nadia into CLM. She was living as a young dependent in her family’s home. Her older sister was the one providing the little food that they had. She was dating a man who’d occasionally make her gifts of money, and those gifts were the household’s one form of support.

But neither the older sister nor the mother qualified for the program. Neither had a child. And we had to do something. So we decided to take Nadia. We figured that we couldn’t count on her sister’s income. The guy could move on to the next woman at any time. And even if he didn’t, he and the sister could decide to focus on themselves.

Micheline lives farther into Chito from Kolonbyè and slightly closer to the river. A mother of seven, her current partner is father only to the youngest. The man comes to see her and his son once in a while, but he has another family where he spends most of his time. The father of the first six children died years ago. Micheline now lives in a house with the youngest four children. The older children are living in other people’s homes. It’s mango season, so the children aren’t as hungry as they are most of the year. But scavenging ripe mangos and washing the mangos that neighbors are preparing to send to market are not reliable ways to feed a household. Approving Micheline for the program was an easy decision.

I also met Julienne. She was the only woman I met during the course of the day who was my age. She lives in a house with three children and a grandchild. Her two daughters are the earners. One has a boyfriend who pays to send her to school and occasionally gives her some cash that she can use to help her family. The other does neighbors’ laundry. They pay her either with food or a little bit of money. The third child is a teenage boy. He’s not in school, and he more or less fends for himself by doing chores for neighbors who give him a meal.

If I had used our original criteria for CLM, I wouldn’t have been able to take Julienne. She has no children who depend on her. But she’s partially paralyzed. She depends completely on her kids because her arms are no use to her. So we can take her as a disabled person. The Kolonbyè cohort is our first attempt to integrate all the persons with disabilities we come across into our program. So after a short chat with Julienne, I approve her for our program as well.

Wilson and I saw about 20 potential members in Chito during the day. We finished mid-afternoon, and we could see the rain approaching from farther east as we were preparing to cross the river once more. By the time we got to the water’s edge, we were caught in a downpour. Fording the now swelling current was a chore. We were already drenched by the time we got near our motorcycles, so there wasn’t much point in trying to wait out the rain. We hopped on and rode away.