On Thursdays, the Labasti market takes over a small section of National Route #3 about five miles south of downtown Mibalè. Merchants of all sorts spill into both sides of the street. Some of them are hawking loads of produce, bigger or smaller, in sacks or baskets or simply piles. There’s clothing, both old and used, hardware arranged in racks or on carts, cosmetics, laundry products, and groceries.

Vendors stroll up and down the road with bundles of brooms or pyramids of home-made chairs loaded on their heads or with homemade racks of belts or sunglasses. Pill-sellers weave through the crowd, their buckets piled high with medications. Bread and snacks of various sorts, both packaged and fresh-fried, are sold as well. Soft drinks and hard liquor. Cooks offer full meals: beans with rice or cornmeal and sauces thick with meat and vegetables. There’s a place to sell livestock at the market’s northern end.

In other words, one can find most of the things that the ordinary days of life require.

Parked vehicles line both sides of the road, adding to the traffic: large livestock trucks from Pòtoprens sent from slaughterhouses in the capital, beat-up pick-up trucks of the sort that carry people and merchandise throughout Haiti, and clumps of motorcycle taxis waiting for fares. Route #3, the route through central Haiti, is now the main – really the only – road out of Pòtoprens northward. The passage of buses and trucks is constant during daylight hours, though only during daylight hours ever since gangs took control of the entrance to the metropolitan area just below Mòn Kabrit. Passage through the market can involve a lot of horns and a lot of yelling.

About fifty or hundred yards south of the market along the road from the main market space, a footpath branches off to the east. It’s a couple of feet wide, made of hard-packed soil. But it’s uneven. Heavy tropical rains wash irregular contours out of it. The thick roots that enter the path from both sides hold the dirt in places, but only in places, which only serves to make the path less even. Dark mud collects in spots whenever it rains.

The path passes three or four small metal-roofed houses on each side before it comes to farmland. The area around Labasti is fertile, and as this path cuts downward towards a narrow, muddy stream, it passes along a couple of patches of corn, pigeon peas, and manioc. Further in, larger spaces are planted with plantain and sugarcane, the crop that has come to dominate in the area. The stream is easy to ford, and the path climbs the opposite bank, continuing upward past a few more homes before a large field of cane opens up on the left.

On the right, a few feet above the road, is a shack falling apart in the middle of an abandoned-looking yard. Behind it and slightly above it is Louimène’s small home.

***

Louimene graduated from CLM in December 2014. Her experience in the program was unusual. She was part of it for just nine months, rather than the usual eighteen, and she received an investment from Fonkoze much less than what her fellow members received. But, even so, she speaks of CLM as an important source of her success.

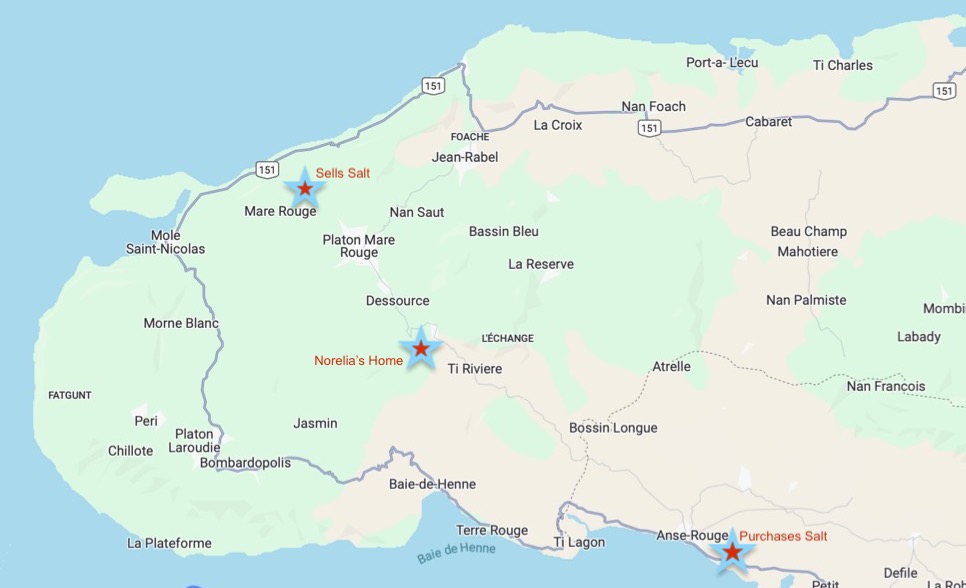

She joined the program later than the other members of the group she eventually graduated with because, right after she was selected, she left Labasti, where she and her partner Lucner had been living. She went off to care for her sick mother in Bouli, an area in the mountains of northwestern Boukankare, the commune north and west of Mibalè. By the time she returned to Labasti, the program had started, and her place in it had been taken by another member.

It was too bad. She, Lucner, and their two boys could hardly have needed CLM any more than they did. They were living in an ajoupa, a straw tent-like structure, in the corner of a field that did not belong to them. It belonged to a farmer who would hire Lucner to help in his fields. Lucner earned 50 gourds on the days that the farmer gave him work. That was about $1 at the time, and it was the couple’s only income. It had to feed two adults and two small kids.

***

Their life hadn’t always been that way. When they met, Lucner was a successful small-time merchant in Pòtoprens. Louimène was a maid in a home near his business. Lucner fell for her, and he lights up when he tells the story. He liked her as soon as he saw her, and he decided to get to know her better.

Louimène’s father died when she was 14. Her mother could not afford to take care of Louimène, so she sent her to live with a family in Pòtoprens. Louimène left the family within a year. She went off looking for a job because she did not like the way the family treated her. “I was hungry all the time. They had a business selling boiled cassava root as a snack. They would feed me the leftover roots that hadn’t been sold.”

She found a job as a maid, which she soon left for what she thought would be a better one. One day, when she was not yet 16, she was sent to his business to buy some rice. Lucner volunteered to deliver the rice himself, leaving the business and his wallet in Louimène’s hands. That wallet functioned as his cash register, and it held all the money from the business, over 7,000 gourds. “I wanted to see whether she was honest.” When he returned from the errand, he found that all the money was still there.

He gave her 500 gourds as a thank-you gesture, and she used that money to buy cookies and crackers, which she began to sell. Soon she had turned those 500 gourds into more than 1,000, even while she continued to work as a maid. “I liked her right away, but when I saw how smart she was I decided to try to make her mine.”

Then one of his brothers became sick, and Lucner returned with Louimène to his home community in the hills east of Labasti, to help care of the man. They spent almost everything they had nursing Lucner’s brother back to health, but then they had to leave the cluster of homes where Lucner’s family lived because Louimène and Lucner’s sister could not get along.

They moved into a room of a house that belonged to a wealthier neighbor, but it wasn’t long before the neighbor wanted them out. “He told us to open the door and the windows to let the mosquitos out.” It was as though they were attracting bugs.

So, the couple threw up the ajoupa, a one-room, tent-like structure that Haitian farmers build out of straw. They got permission to put theirs in a corner of Lucner’s employer’s field. Usually, an ajoupa serves as a temporary shelter for farmers while they work in fields too far from their home to go back and forth every day. But for struggling families like Louimène’s, an ajoupa can become a long-term home.

The ajoupa was the only home that she and Lucner had, and it stood on a plot of land that wasn’t theirs. They had no livestock or other assets of their own, and they depended on the 50 gourds Lucner earned on the days when he could earn it. The CLM staff members who saw them during the selection process gave them the highest possible score for food insecurity, “food-insecure with hunger.” They were going hungry much of the time.

***

But shortly after Louimène returned to Labasti from caring for her mother, a CLM member in a neighboring community decided to move to Pòtoprens, abandoning the program. Hilaire, the case manager who was working in Louimène’s neighborhood, strongly advocated for bringing her in it to replace the woman who left, even though about half of the program’s eighteen months had already passed.

The CLM team was able to recuperate the roofing tin from the woman who had left, pulling it off the framework it had already been nailed to. The staff also retrieved one of her two goats, a small pig, and 1,000 of the 7,200 gourds of cash stipends she had received. All this was given to Louimène, but nothing else. It didn’t give her much to work with.

Haitians say that someone can have to “bat dlo pou fè bè.” That means to churn water to make butter. It’s a way to talk of making something out of nothing. And Louimène and Lucner started churning water for all they were worth.

Lucner kept working hard in in their neighbor’s fields, even as he took primary responsibility for the livestock that Louimène received from the program. Louimène invested the 1,000 gourds she was given into a small commerce. She would buy spaghetti and canned milk, put it on her head in Labasti, and walk the five miles into Mibalè, calling out her wares and making sales all along the way. Normally, she’d sell out by the time she got to town. She’d buy merchandise there for the next day and carry it home. If she was busy — doing laundry or attending a CLM training — Lucner would do the job instead. The business began to grow, and Louimène started investing some of its sales into additional products. On Thursdays, she would find a busy corner of the market to sit in, put her basket of merchandise on the ground in front of her, and sell what she could.

She and Lucner talked to the landowner about the ajoupa they were living in. They needed his permission to improve it. Often even farmers who are open to allowing a poor squatter put up an ajoupa on their land will object if the squatter adds a tin roof. It makes the structure seem more permanent. And Louimène and Lucner wanted to add not just a solid roof, but a cement latrine. They were eventually able to get permission to do so, in part because of their case manager’s help in the negotiations.

***

When Louimène graduated in December 2014, she and her family were eating two hot meals a day. Louimène reported a clear plan for increasing her regular income – she would sell one of her pigs and use the proceeds to add to her business – and she proudly explained that this plan meant Fonkoze would not need to worry about her anymore.

By then, she had sold her original goat and its young. She had acquired a second smaller pig but had sold the first one. She used the proceeds from the sales of the goats and the first of the pigs to buy a cow, which she wanted because she had a plan for that too. “We needed land, and if you buy a small cow you can hold onto to it. While it grows, you wait for someone to sell a piece of land, and when the chance comes along, you can sell the cow and buy the land.”

And that’s exactly the way that things turned out. After graduation, the man who owned the plot they lived on began to resent the family’s presence. “When he saw our cow, he said that he had given us land to put a house on, but not to graze animals.” He started to hire another man to work in his fields and to pressure Louimène and Lucner to leave. Since they had no place they could go, they put up with his humiliations as best they could.

Eventually, however, they found another landowner with a sudden need for cash. They were able to buy enough of a plot to put their little house on for 12,750 gourds. They sold the cow they had recently bought to get their hands on the money they needed. They disassembled their house and reassembled it on their own land, removing the roofing from the home that they had built and reattaching it. They even spent the extra money and effort necessary to install a simple latrine, having learned of its importance.

One of Lucner’s brothers bought the neighboring plot for a similar amount. But when Lucner made the purchase for himself and Louimèner, he was careful to put Louimène’s name on the receipt, rather than his own. “If anything happens to me, I wouldn’t want Louimène to have problems with my family.”

***

That is when things started to get more difficult for the couple. Lucner got sick. He was unable to work for a couple of months. Medical expenses and life without the income he earned forced the couple to sell off their second pig and, eventually, the small commerce that Louimène had managed to create. By the time Lucner was working again, the couple was back almost to square one. They had their own house, and it was covered with a good tin roof, but they had no assets and no small commerce.

They found themselves driven to make a difficult decision: Their children would move in with Louimène’s mother, in Bouli. Louimène would seek work as a maid in downtown Mibalè until she could save enough money to return to business.

She did so for a year, earning 2,000 gourds per month. “You put up with how they treat you, because you know you won’t be doing the work forever.” She sent much of what she earned to Bouli, to help her mother care for the kids, and she spent most of the rest of her earnings keeping herself and Lucner fed.

Once Lucner’s health returned, he could contribute as well, and they could start to dream of bringing their children home. Louimène wanted to bring them back as soon as she had saved enough to go back into business. Looking back, she says, “When they are with me, I can take better care of them.”

Things improved for the couple and their children after they moved back to Labasti together. Though they still had no farmland of their own, they were able to rent a plot. Lucner farmed that plot and worked a second plot as a sharecropper, so they did not depend on day wages exclusively.

Louimène continued to earn money through small commerce. When she first went back into business, she followed the same plan that had worked for her previously. She filled a basket with a couple of products, put it on her head, and hiked five miles into town, selling as she went. But she managed her money carefully, and she soon had too many products to carry around on her head. She decided to start selling out of her home instead.

She sold a range of basic groceries, and she was the family’s principal earner, bringing in enough to feed the family and make weekly contributions to her savings club, or “sòl,” Every week, members of the sòl make a set contribution, and one of them receives the whole pot. Whenever it was Louimène’s turn to receive the pot, she would invest most of it right into her business. Her business would thus grow and shrink cyclically as the date of her receipt of the pot was nearer or farther away. At times, it was nothing more than garlic and bouillon cubes. At other times, she could sell rice, oil, and other staples as well. Its value could vary from as little as 1,500 or 2,000 gourds to as much as 10,000.

But though their income grew only slowly after Louimène graduated, the family’s live changed in important ways. Despite their struggles, they bought a small pig. It was their first investment in new livestock in a couple of years.

And Louimène is quick to talk about another, more important change. She and Lucner married in December 2019. “We got married, and we started going to church.” They couldn’t attend services during the coronavirus crisis, but they prayed with their fellow congregants. Louimène visited neighbors’ homes with other church members every morning.

Between her business and Lucner’s farm income, they also created a different sort of home. They tore down the walls of their shack, which had been made of thin sticks, woven together and covered with mud. They replaced them with walls of palm wood planks in the back and on the two sides, which they painted a creamy orange. They built a new front wall of stones. It was much more solid and attractive than the house it replaced. They also enclosed what had been a covered entry in the front, so the inside of the house was about a third larger than it had been.

Her business was working well, but Lucner’s farming was not. A persistent drought killed a couple of crops. Eventually, he came to doubt whether it was worth replanting. And, so, the couple had to face another difficult decision. Louimène had a brother who was living across the border, in the Dominican Republic. He works for an avocado producer, loading sacks onto trucks, and he told the couple that he could get Lucner a job working with him.

There were just two problems. First, Lucner would need to find 6,000 gourds to pay for the trip across the border. Second, he would have to live away from Louimène and the kids.

Lucner knew he would accept the second problem, as unhappy as it made him. He didn’t think he had a choice, because it was the only way he could think of to earn money to help Louimène take care of their kids. He could not bear not contributing.

The first problem seemed like more of a barrier. He didn’t have the money, and he didn’t know where he’d get it. He felt stuck.

Until Louimène let him know that she had enough money saved up, and that she would give it to him. Lucner went to join his brother-in-law in 2022, and he started to regularly send Louimène as much of his earnings as he could. He visits her and the kids occasionally, and he spent a month with her this past year recovering after an accident, but for the most part the couple must now live apart.

***

And as Louimène herself continued to work hard, her business continued to grow. She kept adding new products. In addition to what she bought in Mibalè, she started selling things she could find at the Labasti market as well. She could buy basic groceries, like rice, beans, sugar, and oil in Labasti. She can buy a moderately large quantity, like a sack or a five-gallon jug, and break it down into the small quantities that her neighbors want. She began buying cooking charcoal, too, 500 gourds’ worth at a time – now less than half of a large sack – and dividing it into 50-gourd bags.

Her business took a big step forward through a friendship she developed with another member of her church. He sells snacks out of his home. Louimène would sometimes send her kids to him for them to buy a treat. One day, he saw how well her business was doing and he approached her with a proposition: he makes bi-monthly buying trips to Elias Piña, the large bi-national market on the border, across from Beladè. He was willing to buy for her as well. He’d even front her the money. It was an easy way for him to increase his sales because he charges her more than he pays. He is basically a retailer with Louimène as his one wholesale customer. And their arrangement enables Louimène to buy more merchandise less expensively than she otherwise could so that her business can grow.

Before each of his trips to Elias Piña, Louimène pays him what she owes him, and they talk about what merchandise she needs. His advances can be as much as 13,000 t0 14,000 gourds, which is a little more than $100. He’ll look for what she asks him for, but he will sometimes see something new that he thinks she’ll be able to sell. This new system keeps her business from cycling the way it would when she depended on her sòl. And Louimène has since found another person willing to buy for her in the DR. The second buyer brings her logs of Dominican salami.

Growing her business is important. All four of her kids are now school age, and although she sent her older girl to live with her mother back in Bouli — the older woman asked Louimène for that because she would now be alone without her — Louimène is financially responsible for all four kids. Lucner’s income is still limited. He is back in the D.R., loading avocados onto trucks with his brother-in-law, but he is still slowed by the accident that brought him back to Labasti for a time.

A couple of years ago, Louimène learned about VSLAs. Former CLM members in her area had been recruited into VSLAs established by the CLM team. We cannot reconstruct why Louimène was not a part of one from the start, but she was eventually encouraged to join one by a friend she has among her fellow graduates. When she joined it, the share price was 100 gourds. When her first cycle as a member ended, the group decided to raise the price to 200 gourds. Since members can buy up to five shares per meeting, Louimène can buy up to 1,000 gourds’ worth each week, which is what she tries to do. She takes out loans from this association occasionally as well.

But folks in the area saw how well VSLAs can work for former CLM members, and the associations began to proliferate. The director of a nearby school established one with a share price of 500 gourds. He and his fellow members decided to make the cycle two years long, reather than the usual 52 weeks. Louimène joined that one as well. Taking out loans in this second association is complicated, but Louimène is happy to use her CLM-founded VSLA for credit and to use this other just for saving. The two-year cycle will end in February 2025, and Louimène already has a plan. She wants to buy a motorcycle that she can rent to a taxi-driver and use to do the buying for her business less expensively.

But she has a new project before her that will involve a lot of expense. The couple’s church has offered to help them replace their current home with a more solid one of rocks and cinder blocks. But the church will expect her and Lucner to contribute a lot towards the one room that they will help them build, and Louimène’s vision is beyond the single room. “My kids are getting bigger. I want them to have their own room now.” When the pastor called her, and told her that the church was ready, she went right into action. She gave the church 20,000 gourds she had been saving, and called Lucner in the D.R.

Even before he could return to Labasti, the church delivered sand, rocks, cement, and rebar. It was all hands on deck, as she and the three children who are with her started carry the materials, one small load at a time, from the drop off point — the nearest to her home a motorcycle can reach — to her own spot of land. Even her little girl was carrying rocks, one at a time, or small bowls of sand.

The other members of her church, motivated by the effort they saw from her and the kids, joined in. “I was so embarrassed. I had nothing to offer them. I sent for a couple of sacks of ice water and cleaned all the crackers out of my business and passed them around.”

By the time Lucner got there, they had cleared a spot in the yard behind their current home to build the new one. They had also traced and laid down a foundation for its two large, square rooms. Louimène sent word to her mother in Bouli that she was feeling exhausted, and the older women hiked down from her home and moved in with Louimène for a week, taking over the housekeeping duties. Work on the home should be finished before the end of November. Then Lucner will return to his job in the D.R.

***

The CLM team tends to point to the training and the coaching that the program includes its most important elements. Plenty of members over the years have agreed, explaining in conversations or in the testimonial speeches they make at graduation that the program taught them to manage what they have and imagine what they could have. Louimène is different. She says that she had a vision when she joined the program, but the animals and the cash that she received as a member gave her what she needed to work with. Hilaire, her former case manager, confirms what she says. And she explains, “Even if you are living in misery, you have to struggle to imagine a plan. If you think something through in your head, it will come about eventually one way or anoth