Barbara lives in Opisa, in the hills between Fèyobyen, the large market to the east of central Boukankare, and Tit Montay, the mountainous region above it. She and her husband live with their four kids in a small house that his parents built. It is the house he grew up in, and they’ve been living in it since his parents passed away. “I haven’t been able to build my own home yet,” he explained, “so my sisters let us live in our parents’ place.”

Their children aren’t in school yet. “You’d like to help your children learn something,” Barbara says, “so they won’t be humiliated down the road.” But she and her husband just haven’t been able to afford to send them. The schools in Boukankare aren’t that expensive. There are places they could send the kids for only a little more than $30 for the year. They’d have to find a couple more gourds for books, uniforms, and sneakers, but it wouldn’t amount to that much. But it’s money they don’t have. They use family planning now, she says, because “things aren’t going well. It’s a struggle just with the kids we already have.”

Barbara explained that as she started to have children, she had to figure out a way to keep them fed. “When your children are crying at your feet, it breaks your heart.” So she looked around, and had an idea. It turned into a steady activity, at least when there’s been some rain. She goes into the fields above her home early each morning and collects edible greens that grow wild there. Then she rinses them and brings them to market, earning between $1.25 and $2.50 in a day.

Her husband can earn more than a dollar on the days he finds work in his neighbors’ fields. Between the money they earn, and the little food they can harvest from the small garden behind their home, they do the best they can to keep their children fed. On days when they have nothing to give, the children can sometimes get something from their aunts, but Barbara and her husband just do without.

Barbara, with her husband and one of their daughters.

Barbara, with her husband and one of their daughters.

Beverly lives with her husband and their two daughters in Viyèt, a wooded, hilly area just northwest of Difayi, one of Boukankare’s small towns. Their second girl is less than two weeks old; she has not yet been carried outside of their small house, nor does she even have a name.

Beverly is something new for our CLM program: a second-generation member. We’ve had mothers and daughters who are members at the same time, just as one would expect we would. Extreme poverty runs in families. The unwritten rules of disinheritance, of exclusion, are as rigid as the laws that rule the passage of property from parent to child. But Beverly is different: Her mother is graduating the program, having successfully removed her household from extreme poverty just as Beverly is joining us. It’s not what one would hope. We like to believe we are helping families help themselves once and for all. But her case is easy to understand.

She didn’t grow up at home. She’s her mother’s oldest child. Their dire poverty forced her to send Beverly to be raised by a wealthier neighbor, who had a home and a business in the nearby city of Mirebalais. There, Beverly grew up as a servant. She never was paid. She was not sent to school. But she was fed and clothed, which was more than her mother could do for her.

Just as her mother was joining CLM, Beverly became pregnant. The woman who had raised her, sent her away, and she and the father of her child were left without a place to live. Her mother had just moved to her father’s land, and the old man gave his granddaughter a little plot to live on as well. Beverly’s husband built a small house, and there they have remained.

It hasn’t been easy, though. They have no land of their own to farm. The husband has worked land as a sharecropper, but he was sick during this past planting season and, so, never got anything into the ground. Beverly learned to run a business by watching the woman whom she served, but without any capital to invest, she hasn’t been able to get anything started. They have no animals.

So they’ve been hungry. Even as the infant grew within her, even in the days since she gave birth. She wraps her stomach tightly before she goes to bed because it relieves some of the hunger pains.

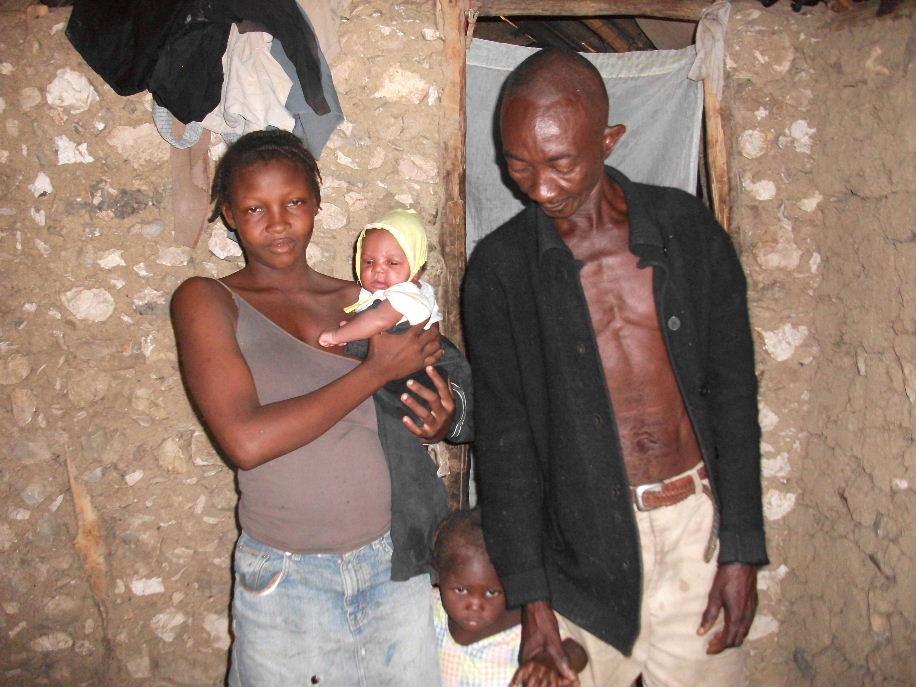

Beverly, with her husband and their two daughters.

Beverly, with her husband and their two daughters.