For Ellen and Carol

Sometimes I wonder, “What were those people thinking?” The “those” might be almost anyone. It’s a type of thought that occurs to me often enough, a sort of formula-half harshly judgmental, half genuinely mystified. Friday, “those people” were whoever brought the jawbreakers to the orphanage.

I’ve been visiting an orphanage every Friday morning. I call it an orphanage, but that misses the mark. It’s a facility that receives abandoned and desperately needy children. The sisters who run it organize food and medical care for infants and young toddlers on the brink of starvation and dehydration. The children-if they live-might be adopted. They might be placed in what would more properly be called an orphanage. Or their parents themselves might take them back.

Jawbreakers seemed a terrible idea. There weren’t nearly enough for all the toddlers and older children. The children, to their credit, are devoted to sharing. This is especially striking because they have so little to share. Jawbreakers, however, are not easy to share. So the kids were taking turns sucking on the ones they had. Then someone figured out that you can shatter a jawbreaker if you throw it hard enough against a bare concrete floor. I should say that the sisters and their staff work hard to keep the place minimally clean, but even so the floor seemed not quite sterile. The shards of wet candy that the kids were passing around didn’t appeal to me. Several were offered. I declined. In addition, as the kids threw the jawbreakers around, someone discovered their military value. They became projectile weapons in the kind of playful fighting that is common among kids.

I go to the place each week because I like the children. For example, there’s Charles. He’s a small boy who must be eight or so. He strolls around the facility, watching the sisters and their staff at work, chatting with various adults and children, always in good cheer. His demeanor, his posture, the way he has about him suggest more than anything that of a “hands-off” administrator, make his or her presence felt in the place where he or she is

the boss. Charles’s twisted, crooked, discolored teeth do little to make his constant smile anything but beautiful. It’s a big smile, above a little chin that rests above a large, bulging goiter. Another example: There’s a little boy of about two perhaps, not quite toddling yet, who does little but point his finger to show that he’d like to leave his crib in your arms. He glowers when you don’t pick him up, and he screams when you put him back. There’s a mute little boy or girl or five or six -I’m not sure about the gender-who walks around smiling and cooing. Other children warn me not to take food from his or her hands, not to let her touch me at all. They say he or she handles his or her own excrement. I don’t know whether that’s true. There are girls and boys who want nothing but to be held, or be carried, or be paid attention to for a short while.

In fact, there are dozens of such children, thirsting desperately for attention. Those of them who can walk around struggle to cling to me as soon as they see me. They want to be touched, want to be held, want to be spoken to. The sisters and their staff have enough to do to keep the children clean and fed. With the best of intentions, they can’t do much more than that. And it’s not clear that they should do much more. The nicer the facility is, the more it might encourage people on the edge of despair to choose not to raise their children.

So I stroll in, and then I sit on the floor, as out of the staff’s way as I possibly can. I don’t try to stand, because standing I can only hold two kids, and I’m too tall to relate well to those I am standing above. Chairs don’t help much. Only three or four can make their way around me if I’m in a chair. If I sit on the floor, and stretch out my legs, five or six or seven can climb on me at once. I can be chatting and joking with them face-to-face,

eye-to-eye. One consequence of their terrible, terrible need for attention is that they pay more attention to me than anyone ever has. I ought to admit that I like them for that, too.

Their need for attention seems infinite. It’s not just that there are too many children, even though there are. Even with six or seven climbing on me, they’ll be others crying because they can’t get as close to me as they need to. But it’s more than just the number of kids. Many of the individual kids seem so needy that one could hardly ever do enough for them. There’s one girl who’s always crying anytime she’s not the only child I’m holding. She needs someone all to herself, and needs that someone to give her much more than I

have.

This brings me to my point. Or points. I have two.

First, I’m in awe of the women who work there. Each one of them might be responsible for a room which has 15-20 cribs, each with a young child who is surely always needy in one way or another. In a sense, the most reasonable response to the situation they’re in would be to leave it. They have, as we say, “only two hands.” And 15-20 kids need food, need water, need to have their diapers changed. And those are only their simplest needs. But the women don’t give up. They keep working, walking from crib to crib, doing what they can for each child in turn. Generally, in good cheer. They seem to know something that I’d like to learn and to learn well: that hopelessness is a luxury, and a stupid one at that. In the face of continual, particular needs, larger questions, global questions, such as “What’s the use?” are trivial.

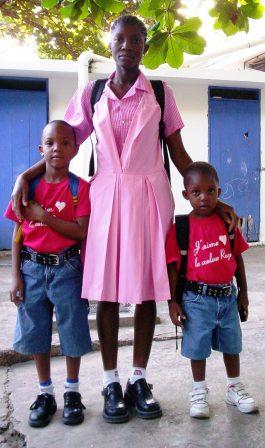

Second: I do enjoy my visits, and I think the kids enjoy my visits, too. And even the staff seems amused by my presence. Or at least they seem not to mind. But it’s perfectly clear that what each child needs is not a small share of a middle-aged bachelor’s attention during the few hours a week he can drop by. Each of the children needs parents, totally committed to him or to her forever. Whether those parents must be Haitians or should be Haitians or whether any parents will do is an important question that I can’t answer, but that is, I think, what each child needs and deserves. I’m smart enough to know that that is not what I have to give.

Which brings me to my cousins, to two in particular, a couple who have raised two magnificent young men, men on the verge of going out on their own. This couple has decided to start all over again, to adopt two infant girls. Cambodian girls, it so happens. They’ve chosen to make a life-long commitment to two more kids. Instead of wallowing in the infinity of needy children, or in any individual child’s infinity of need, my cousins have chosen to assume specific and unlimited responsibility for two particular kids right now. I am in awe of these cousins, too.

As for the jawbreakers, I doubt whether that foolishness really did any harm. I myself am considering a box of superballs. Bouncing off bare concrete floors and walls, they should cause chaos enough.