My grandmother has been very unwell. It’s hard for me to be clear just how unwell because I’m overseas and hard to reach.

She’s 93, so I suppose it’s not surprising that she’s having problems. Nevertheless, until about a year ago the most that you could have said is that she had some trouble with her memory and that she was increasingly prone to being confused. It was not without difficulty that she attended our family’s Passover Seder last spring, but she seemed to have a great time. She’s always had a particular affinity for small children and our Seder was well-stocked with them. A committee of four very energetic little girls made sure that my sister’s house, which is where we met, was very much alive. And my grandmother too came alive in their presence.

By the time I saw her in September, on my way back to Haiti after a visit to the States, she had deteriorated. She seemed more lost, less lively, more fragile. And shortly after that she fell. She broke her ankle and needed surgery.

The surgery is proving to be a terrible challenge to her system. When I rushed back to the States in October to see her, she was miserable. She seemed to recognize me at moments, but not all the time. She wasn’t interested in eating. She was extremely confused, unable to understand where she was or even to recognize that she had broken her ankle and was incapable of walking. It was rather soon after her surgery, and I hear some suggestion that she’s making progress, but it’s hard to be optimistic, hard even to know what to hope for.

I am writing at such length about my own sad news in part because I always try to write about what’s on my mind, and my grandmother is foremost on my mind these days. At the same time, my feelings about my grandmother provide the frame within which I am trying to face the other sad news I’m dealing with right now: the decline in health of Madanm Marinot.

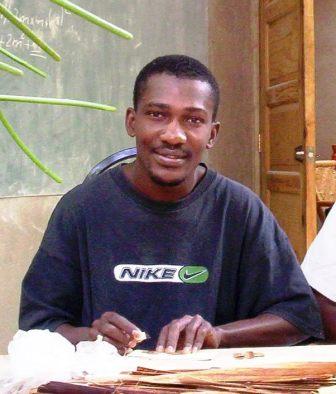

Madanm Marinot is my makomè. I’ve written about the word before. In its narrowest sense, it would mean that she is my godchild’s mother. By the word can have more extended meanings as well. In this case, she is my godson’s grandmother. Her son, Saül, is my very close friend and monkonpè. His son, Givens, is my godchild. And for about a year, Madanm Marinot’s been calling me “monkonpè” as well.

While she’s a good deal older than I am, she’s a long way from being old. I suppose she’s around 60. Saül is the oldest of her seven kids, and he is only 36 or 37. I used to know exactly.

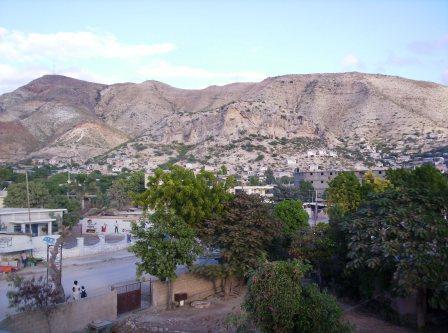

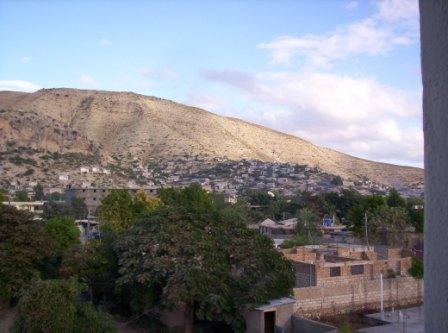

But her health hasn’t been really good for several years. She’s diabetic and suffers from high blood pressure. So at the moments when I’ve seen her over the last couple of years, whether at Saül’s house in Pòtoprens or at her own home in Ench, she’s been a little bit lifeless: quiet, inactive, depressed.

Only someone who’s known Madanm Marinot can appreciate how odd this is. She was previously an extraordinarily dynamic person. Almost too dynamic. She was a hurricane. The first time I visited her home in Ench, she was dizzying: running around, shouting order after order at her own children and the other members of her household, assuring that everything happened just as she thought it should. It was a little hard to take, even though it was all being done for my benefit.

But in October I visited Ench with Papouch, and she was an entirely different person. She spent most of our visit lying quietly in a bed, in her home’s back room, as her daughters looked after Papouch and me. (See: PriviLege.) At the end of our visit, she apologized tearfully. She was upset because her health had not permitted her to receive us properly as guests, this despite the lavish hospitality her daughters had displayed.

The problem was that she had recently had surgery to removed a non-cancerous lump in her breast. The surgery had gone poorly and she wasn’t healing well. She was tired and in pain. Shortly after our visit to Ench, she went back to the hospital in Piyon, where the surgery had been performed. They recommended a new biopsy, for which she would need to come to Pòtoprens. The lab work would be done in the States. She waited for the results at Saül’s house in Pòtoprens. The news finally came in that there was nothing non-cancerous about her condition at all. She has what appears to be an advanced case of breast cancer, and it’s not yet clear whether there’s anything that can be done. Right now she’s getting painkillers and nothing more.

Of course the news has been dreadful for her family, just as my grandmother’s recent decline has been terrible for mine. My monkonpè had tears in his eyes last week as he told me of his mother’s situation.

But things are a little bit different here. Since she has no health insurance, her children are having to pay for every bit of care she gets. And though there is no comparison between the cost of medical care in Haiti and its cost in the States, there is also no comparison between the resources available to my grandmother and those available to Madanm Marinot. Her three youngest children are still in school. She, her husband, and her older kids are funding their for-them-expensive educations. The next oldest child, her fourth son, would like to return to school as soon as possible. His education was interrupted because of his own health troubles, but he’s much better now, and is anxious to move on with his life.

That leaves her three oldest sons, but the middle of them is a farmer and cattle merchant who barely gets by on his own. So she has just two children who can help her, Saül and his younger brother Felix. But there is only so much they can do. Not only are their own financial resources quite limited, not only do they already go to extraordinary lengths to support their siblings, but they are both married and both have children of their own that they must think of as well.

When a doctor suggested that they take her to a final specialist, an oncologist who could evaluate whether she’s a candidate for chemotherapy, her children didn’t hesitate. Her youngest son, a twenty-something medical school student named Job, made the appointment and took her there. But she wasn’t able to undergo the tests that would determine whether chemotherapy would stand a chance of helping her. She was too weak. And even if it could help, it’s not clear whether she, her husband, and her children could afford the expense.

Job, with whom I am especially close, spoke to me at length about how very distraught he is by it all. He insists that he and his family have no right to leave anything untried in their efforts to help their mother, but there is very little he can do except insist. He is not yet supporting himself, and so he’s very far from being able to contribute financially to his mother’s care. When I asked him to say, straight up, whether he thinks his mother would accept the one financial contribution he could make – sacrificing a year of med school so that the tuition money could be spent on her care – he had to admit that she never would agree.

So we are all simply waiting. Madanm Marinot now insists that she wants only to return to her home in Ench to await whatever may come. She is still entirely lucid, so unless something changes the family will probably try to accommodate her wish.

My mother and father have been forced to take full responsibility for my grandmother’s life and well-being. It’s a sad thing because my main memories of my grandmother are of a very loving woman, both capable and strong. Her grandchildren – my sister and brother and I – all live too far away to offer our help. I know it’s hard on my parents, but they have Medicare, doctors, nurses, my grandmother’s excellent financial advisor, and probably others as well working beside them. At times, the very task of managing such a scattered team must itself be a burden, but I’m glad they have access to such assistance nonetheless.

Madanm Marinot’s family is able to huddle around her in her time of need. She doesn’t lack for their time and attention, but it’s not clear what any or all of them can do.

As I said: We simply wait.