It’s surprising to discover how many people believe that Newton’s laws of motion are false.

I’m not thinking of people who’ve read Einstein or other modern thinkers and who have learned to see the laws’ limitations. I’m thinking rather of people who discover, as soon as they begin to think about the laws seriously, that they just aren’t convincing.

Yesterday’s discussion at Kofaviv offered plenty of instances. We spoke, among other things, about the way Newton explains one of the laws, that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The women especially wanted to talk about an example he uses: that if a horse pulls a rock, the rock pulls the horse just as much. Some of the women thought the claim simply absurd: Rocks, they said, do not pull horses. Most of those who opposed that objection did so by denying Newton’s claim in another way: They said that a rock could pull a horse if it was big enough and if it was falling, rather than sitting still. But that very defense of Newton’s claim still implied that either the rock or the horse would do the pulling, not that a paired action and reaction, always equal, would always be taking place.

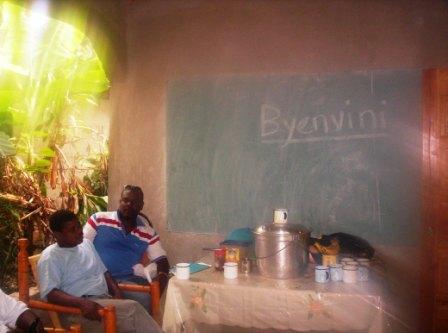

As the meeting began, it had felt a little odd that we were to talk about Newton’s laws at all. We meet on a patio in front of Kofaviv’s main office, and that patio is also a waiting room. Women and girls who come to Kofaviv for the services it offers sit along the wall, outside of our circle, while we work. Kofaviv, the Commission of Women Victims for Victims, is a group of women who have suffered rape and other violence. They organize a range of counseling, medical, and advocacy services for other rape victims. So the women sitting with us on the patio as we hold our meeting are rape victims, young and old, and their presence and the images it calls to mind force one to ask whether a text on classical mechanics is really worth talking about. Shouldn’t we be more focused on the difficult problems they face every day?

That’s a serious, not a rhetorical question, and taking it seriously means asking what the texts we use in our discussions are for. Folktales from around the world and Haitian proverbs might not seem to force the question quite as starkly, because they let us feel comfortable as we talk about them in a way that Newton’s laws do not. Tales can be entertaining and, in Haiti, even when proverbs are curious, they’re always familiar. But neither relates more directly to the horrible reality the Kofaviv women have all suffered than the Newton does. The best way to explain what the texts we use are for is not a lot of theory, but an account of the work we did on Newton, so I want to talk about that meeting.

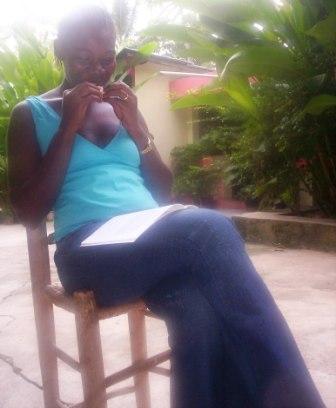

I rarely lead these meetings now. Usually, they are led by volunteers from among the women. We’ve been working together since February, and it has seemed appropriate, even important, to encourage them to take increasing control of our activity. The meeting on Newton’s laws was led by Adjanie, a young woman expecting her first child. I had worked with her two weeks ago, and she had run off every 15 minutes or so to throw up, but she seems now to be over that.

Adjanie started us off, even before having us read the text, by asking us to think about what a law is. She invited us to sit quietly for a few minutes as we thought. After about three minutes, she had us divide ourselves into groups of three or four to discuss our answers.

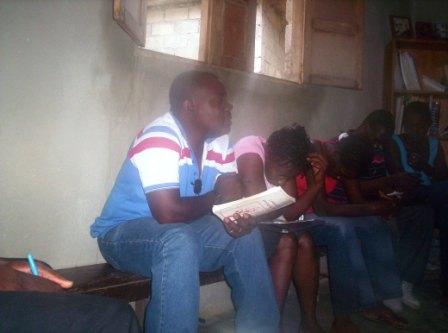

These conversations were animated and interesting. Though I was in one out of the four small groups, it was easy to see that everyone was very much involved in the work. Small group work is an extremely important part of what we do. It allows several people to speak at once – one in each group – and so facilitates broad participation; it encourages quieter participants, who might initially be afraid to speak in front of a large group, to start talking in a less intimidating environment; and it forces participants to start talking to one another without the group leader’s mediation.

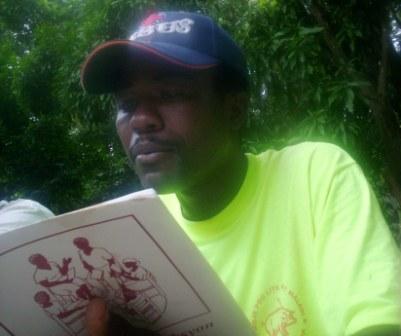

After about 15 minutes, Adjanie had each group give a report. This led to a short conversation about how laws help us and hinder us in our lives. The women drew examples from their own experience: They spoke as mothers of making laws for their kids, as citizens of the laws their political leaders make, and as victims of ways in which various kinds of armed men make rules in the neighborhoods where they live.

Adjanie was now ready to read us the short text. She asked another woman to reread it for us, and then invited us to think about it individually as we read it a third time in silence. After a couple of moments, she started us off by asking what we thought of Newton’s laws.

For the next half-hour, we talked about whether there are exceptions to the laws, whether a rock can pull a horse, whether the right way to characterize the effect of gravity is to say that it makes objects “fall” or makes them “descend,” whether natural laws are like the laws that people make, whether natural laws are useful in our lives, and whether we can throw rocks in a straight line. In other words, we spoke of everything from details in the texts to broader issues.

What was most striking was how the group spoke. Participation was broad. Nearly everyone talked in the course of thirty minutes even though only one person spoke at a time. The women listened to one another, responding to one another directly and encouragingly. The couple of times that the conversation degenerated, Adjanie said nothing but “Remember the rules of the game,” and order was quickly restored.

The text had given the women something to talk about. It raised questions that invited them to talk about their experiences – like whether natural laws and human laws are useful – and other questions that simply invited them to let their imaginations go to work – like whether a rock can pull a horse. Both sorts of questions provided opportunities for the women to work together: listening, encouraging, questioning, responding.

The result of the work was all the more striking on Tuesday because it was my second meeting of the day. Earlier I had met with a group of Haitian professionals, the staff of an important NGO. It was the first of planned weekly meetings, and the text we used was an engaging little folktale. These professionals interrupted each other constantly. They spoke two or three at a time. They spoke to me, the group’s leader, rather than to one another. There was, in other words, very little listening, very little cooperation.

The women of Kofaviv have made very good use of ten months of texts. The texts, both the excerpt from Newton’s laws and the others, have helped them learn to speak with one another, to listen to one another, to work together. If all groups worked together the way the Kofaviv women do, the world would be a very different place.