Saturdays can be physically challenging. On the weeks when I visit Lagonav, I generally rise at about 2:00 AM so I can get down the mountain in time for an early boat. About the trip down the mountain, suffice it to say that, if there’s a moon and if I don’t have much baggage, walking a few hours is a tempting alternative to the bone-rattling truck ride. When I get to Pòtoprens, I go straight into Site Solèy, where I have an increasing range of groups and individuals who are asking me for my time. I grab a cup of coffee when I get there, and am then on my feet, talking with young people, most of the day.

The contrast between the two communities could hardly appear to be greater. Both are poor, but that’s where the similarity stops. Matènwa, my base on Lagonav, is a very rural place; Site Solèy is a crowded urban slum.

At the same time, a series of experiences in the two places over a couple of days brought to light a single principle. It’s an assumption that guides almost all of my work, so it’s interesting to me to see it exemplified in different ways. One way to state the principle is like this: People make progress through their own activity.

I spent some of Thursday afternoon with Catheline. She’s a first-grader at the Matènwa Community Learning Center. An orphan since her father died, her mother sent her and her older sister to Matènwa, where they live with their paternal grandmother.

Catheline was counting her fingers, tallying one hand, and then moving to the other, as people normally do. But she kept getting different answers. One time it would be seven, another time nine, and a third, eleven. She was having a hard time keeping track of which fingers she had counted. She just wasn’t seeing the array of them clearly. She giggled after each new result, but it wasn’t joyful laughter. She seemed to recognize that she could only have one quantity of fingers.

Finally, she did something I’d never seen. She placed her hands together palm to palm, with her fingers spread. She counted her two thumbs, her two index fingers, her two middle fingers, her two ring fingers, and her two pinkies. She reported the new total, ten, with a big smile.

By thinking about the problem she was facing, she had discovered her own solution. She found a way of keeping good track of her count. She was proud of the certainty she felt. When I asked her the next day how many fingers she has, she answered correctly without hesitating.

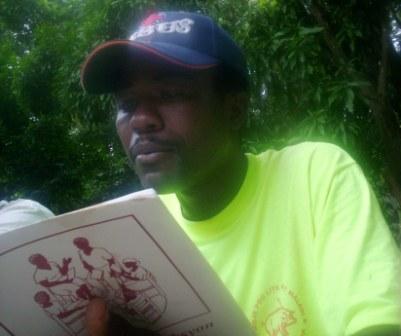

Friday I was working with the Matènwa teachers. We are learning to use the microscopes they have. The microscopes have been at the school for some time, but they haven’t been used much in the classroom. I am very far from being a skilled microscopist, or even an unskilled one, but I’ve taken as many science classes as most Americans. I’ve even taught a few. I also had a microscope as a kid, and I remember how much fun it was to look at all sorts of stuff.

We started by working on the basic techniques they would need: preparing slides and focusing. Though these are things that one could continue to improve at for years, especially slide preparation, nevertheless five or ten minutes of coaching is more than enough to get one started.

For the teachers, seeing things, like an ant, under a microscope is, first and foremost, a spectacle. Their initial temptation is to let their excitement be the center of the experience, to just leaves things at “Wow! Isn’t that cool?” and then to look at something else. I wanted to help them slightly change their focus. Rather than seeing the microscopes as the wonderful toys that they are, I wanted to help them see them as tools of investigation. So I had given them homework. They were to identify a question that they wanted to answer by looking at something under a microscope. They would write down the question and the answer that their study revealed.

The most interesting answer came from Fritzner, a teaching intern visiting the school from the Haitian mainland to learn how the Matènwa teachers work with kids. He had wanted to know how many legs ants have, and had learned that they have ten.

Fritzner had not been the only teacher interested in looking at ants. Robert had look at them as well. So had Isaac, another intern. They each reported that they had seen only six legs. So we all went back to the drawing board together. Fritzner hypothesized that the way his ant had been curled up on the slide had confused him, so the teachers talked about what they might do to ensure that they were getting a good, clear look. They decided to use a drop of water to spread its legs.

It was not long before our judgment was unanimous. Ants have six legs.

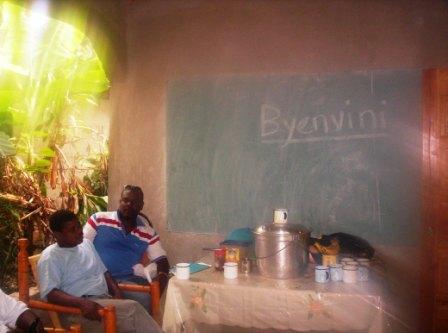

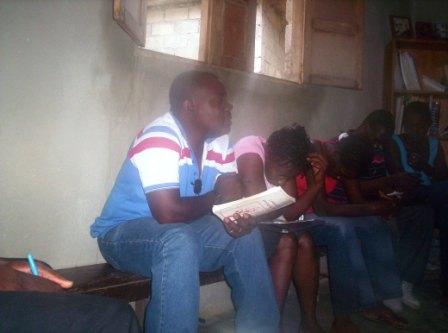

Twenty-four hours later, I was in a hot, cramped second-floor hallway in Site Solèy. I was talking with about a dozen young guys, teenagers mostly. It was our third conversation. In our previous meetings, they had asked me to organize them and to give them a mission. They had insisted that they had nothing, that they were capable of nothing. They needed a savior, they said. They used that very word. And they had chosen me.

I was, of course, put off by the thought that a group of guys I hardly know, who live in circumstances I can hardly imagine, were looking to me to change their lives. I had insisted through our conversations that I could give them nothing but my time; they had responded that they needed much more. I should add that I’m sure they’re right: There’s precious little that residents of Site Solèy don’t lack. But I don’t have the resources to even begin to address all, or even some, of their needs properly.

So we focused in our second conversation on their desire to feel organized. They wanted me to help them create an organization. They even thought that I should give it a name. But I tried to talk about what it means to be organized. I spoke about organizations I’ve seen. They have by-laws and hierarchies. They might have a president, a secretary, a treasurer, and more. None of that actually means that they’re doing anything.

The Site Solèy guys, on the other hand, as lost as they felt, were already organized in a very important way. Every morning, they put together whatever little money they can find and buy the ingredients to make a very simple meal. And then they share it, even, as they explained, if everyone gets only a single spoonful.

I explained that as soon as they set out to accomplish some specific goals that they set for themselves, they will discover they are already organized. They’ll discover that the tasks themselves will organize them in a much more meaningful way than by-laws could.

And we talked about things they might try to do with the resources available to them. One idea that came up was spending a day clearing away litter from their street. They complained that they would need wheelbarrows, shovels, and brooms, all things that they don’t have. I told them that they should consider either how to get hold of such things or how to make do without them. They seemed so pessimistic about themselves that I wasn’t sure what, if anything, they would try.

When we met Saturday, the first thing they wanted to say was that they had spent Wednesday cleaning up the street. They had used sticks, pieces of cardboard, beat-up old buckets, and their bare hands. They had divided themselves into teams, with various responsibilities, shifting duties as the day went on. They seemed happy with the result, and said they would make clean-up a regular activity.

If I had had any doubt at all about their sense of accomplishment, it was washed away by something that happened when the conversation closed so we could start the English class I had promised to give them. These are young men live in what is sometimes cited as the worst slum in the hemisphere. They have no work and are not in school. They are underfed and have limited access to healthcare and safe water. Their neighborhood is subject to flooding, and poor sewage ensures that mud is the best part of the oozy fluid that sometimes covers their streets. But when I asked them, in Creole, what the first thing they wanted to learn how to say was, they replied, without hesitation, that they wanted to know how to say, “What a beautiful day.”

I could have told Catheline that she had ten fingers. Her big sister, Sondie, was trying to do just that as she struggled. But taking in an answer passively would not have accomplished what the solution she discovered did. By facing and overcoming the difficulty herself, Catheline developed more than new knowledge. She developed as a thinker, as a problem-solver. And her happiness shows that, at some level, she was excited about that result.

Fritzner and the rest of us could have learned that ants have six legs from any book about insects, but the lesson would not have been the same. Rather than just capturing information, we had experienced what it means to investigate. And Fritzner had learned a more important lesson that he was able to clearly express: What you see depends very much on the care with which you prepare your slide. That is to say that real investigation is not the business of what we now call “couch potatoes”, but exacting work. A textbook could never have taught him such a thing. When he wrote up his homework a second time, he included a very detailed drawing of a six-legged ant. He was learning to look with care.

Listening to the guys from Site Solèy say to each other, one after another, “What a beautiful day!” was a stunning result of their own achievement. It’s hard to imagine anything that someone could have done for them affecting them in quite that way.

The work in Site Solèy will continue to be challenging. I try not to fool myself. They may need help choosing objectives that challenge them more and more without overwhelming them. And despite everything I’ve told them, they surely still have expectations that, at some point, I will invest much more with them than time. That would be only too natural for struggling guys who befriend a wealthy foreigner who enters their midst. But by being as clear and as frank as possible, both about what we expect and what we intend, we should be able to move forward.