I had a pretty likely hunch as to what the problem we were facing was, but I wanted to be sure. I also wanted to hear it from the folks I was working with. So I started the conversation by asking, in a sense, why we were meeting together.

I had been invited to Fayette, a small rural area outside of Darbonne, which is outside of Léogâne, which is outside of Port au Prince. I was asked there to talk to a group of teachers about how they could use the dialogue techniques they have learned through the practice of Reflection Circles in their regular classes to teach subjects like math. They were particularly interested in the small group work that Reflection Circles always include. I have been meeting on and off with these school and adult literacy teachers for three years. For what seemed like a long time, my partner Frémy César and I were going to Fayette almost weekly, helping the team study discussion leadership.

So the teachers knew very well how to use Reflection Circles and the small group work they were asking about, but they were somehow hesitant about using a technique that they’ve already mastered to face a problem they have not faced with it before – like how to teach math. This was true, even through they very much wanted to do just that.

The question I started by asking was not, therefore, just “What are we doing here?” I was able to give that question more precision by asking why they, as experienced as they are, don’t feel as though they can use Reflection Circles for math, and the answer was predictable. Miracle, one of the teachers at the new community school in Fayette, is the one who spoke up. He said that Reflection Circles is just about opinions, whereas when we do math, even if we pursue different routes, we are required to come up with the same answer nonetheless. How, they wanted to know, could a conversation teach a precise, inflexible skill?

His answer was, from my perspective, a stroke of luck. I couldn’t have anticipated that he himself would make reference to the way that different routes to the same answer are possible. So I made a claim: The real mathematical moment is not in the correct use of predetermined methods of calculation. I said that what is more important in math learning is the discovery of means to resolve mathematical problems. And I added that such discoveries could be effectively developed through small group work.

I had to be careful. People here, just as in a lot of places, can be inclined to hear things in black and white terms. The last thing I wanted was for them to think I was saying that right answers don’t matter. So I tried to really emphasize that what I was proposing would remain one part of an approach to teaching math and that the exercises, sometimes repetitive, that they assign their students would remain important. But I wanted them to think about the way they typically teach math and consider whether other means were possible.

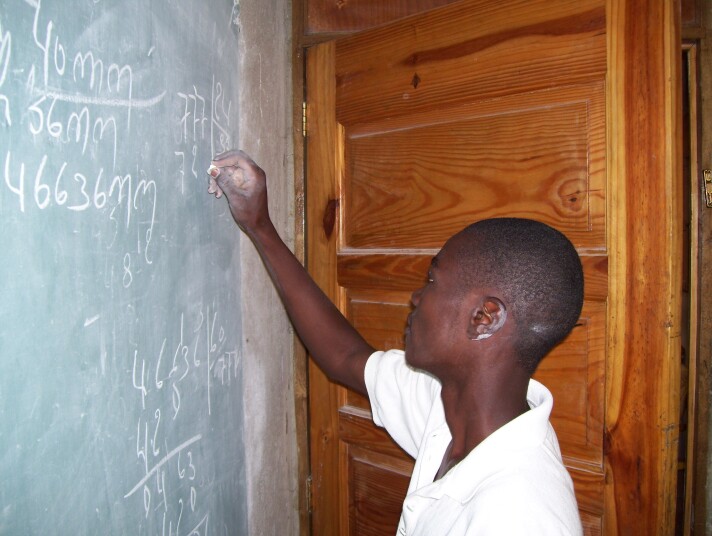

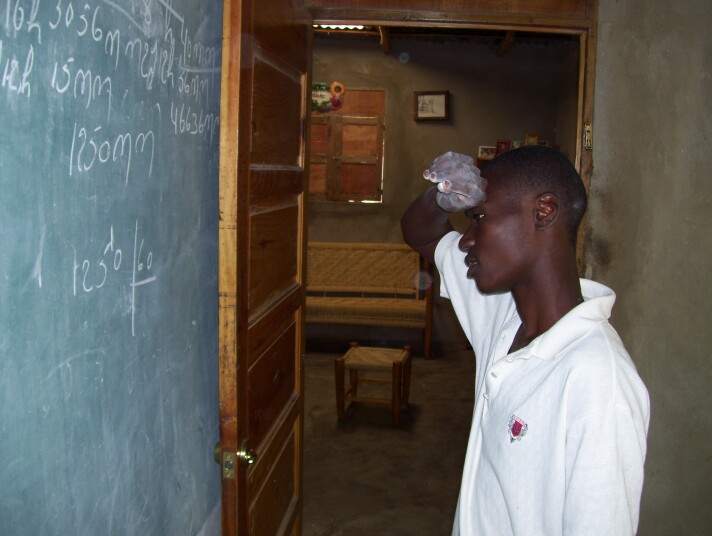

This is the way math classes in Haiti tend to work: The teacher puts a problem on the board, almost certainly in French, and then solves it. The students copy it into their notebooks, and then study it at home. The teachers might also assign two or three similar problems as homework. I asked the teachers why they couldn’t put a new problem on the board and then divide their classes into groups. The groups would have the task of figuring out how to solve the problem. Each group would present their solution to the rest of the class. The class – including its teacher – would pose questions to groups about their answers and the reasonings they used to find them.

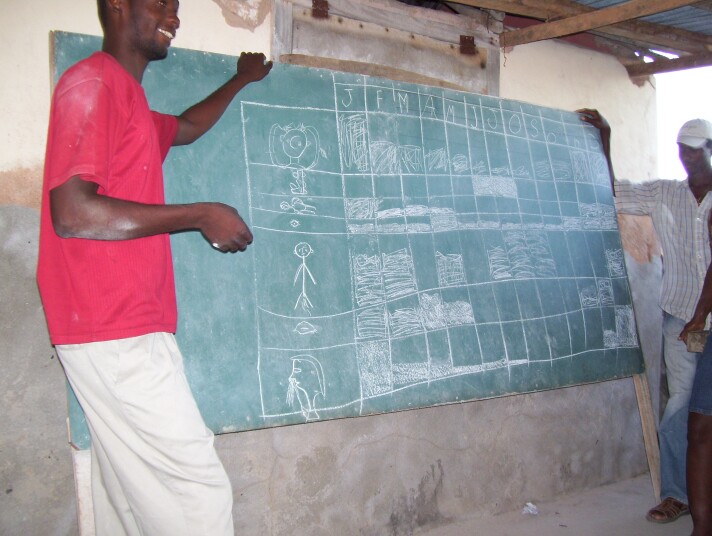

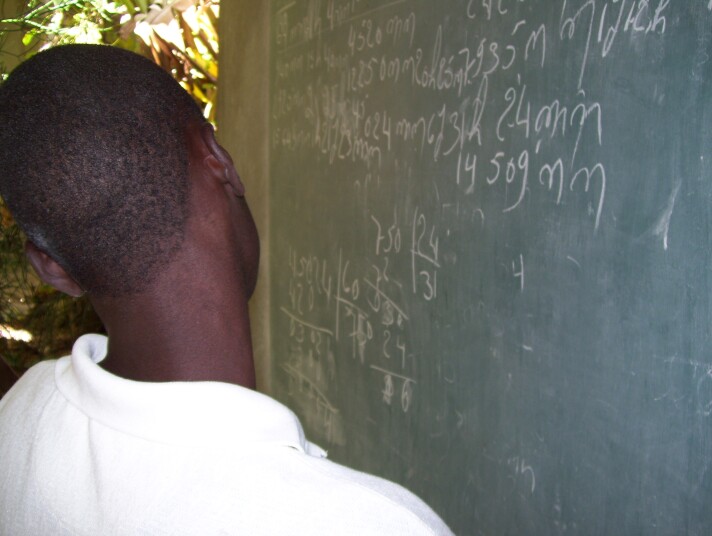

But all that was just my talk, and though the teachers said they understood and liked what I was saying, it seemed important to try putting things into practice. So we divided into groups. I asked each group to develop a problem that they felt would be appropriate for the level of students they teach. We would then exchange problems. Each group would take one of the problems another group had created and work out at least two different methods for solving it.

I emphasized this last point. Even though they said that they recognized different routes could be valid as long as the answer they arrived at was correct, it would be hard for them to really feel that until they were faced with multiple correct routes.

The exercise turned out to be harder than they had anticipated. A couple of groups proposed problems that could not be solved because key information was missing. The groups who were asked to work with those problems had to add assumptions, which they specified as part of their presentations. For example, one group proposed the following problem: “A man bought six cows for 20,000 gourds apiece. One died before he could resell them. How much should he sell the five surviving cows for?”

The first participants who understood the problem wanted to say, very simply, that he should sell them for as much as he could get. And they were right. But then they decided that they would do a calculation based on an assumption: namely, that the man should retrieve what he spent for the six cows.

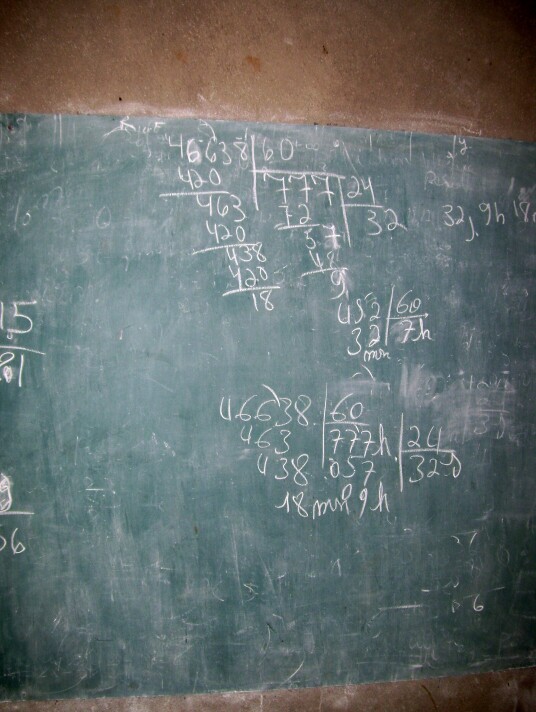

So they divided the 20,000 gourds that the dead cow had cost him by five, the number of living cows, and added that quotient, 4000 gourds, to the price of each cow. The answer they got was 24,000 gourds. And they had little trouble fining a second way: One member of the group multiplied 20,000 gourds by six cows. He then divided that product, 120,000 gourds, by 5. He got the same 24,000 gourds for an answer.

The groups with simpler problems, however, had a much harder time coming up with two routes. The problem that caused the most trouble was the following: “A women buys six dozen notebooks for 250 gourds, buys 55 gourds worth of pens, and buys pencils for the same amount of money that she spent on notebooks. How much did she spend in total?” The group simply did the addition: 250 + 55 + 250 = 555 gourds. They could see no other approach.

After they presented their solution to the group, they admitted that it was the only one they could think of. Job, who had seen that he could multiply and divide the cows jumped right in: He would have multiplied 250 by two, and then added 55. His route was not very, very different, but it was different nonetheless.

In talking over the results, the teachers said they were pleased by our work. Marjorie and Emmanuel both said that they really hadn’t understood what “different routes” meant until Job made it clear. Thomas talked about his own experience as a schoolboy, when a teacher had seen him attack a multiplication problem through addition. He had gotten the right answer, but the teacher hadn’t even looked at anything beyond the fact that he hadn’t applied the method the teacher had expected. Thomas was excited to see us validating the sense of things he had developed way back when.

All this had to happen in a couple of hours. We only had half a day, and that meant much less than half a day because everyone had to get to Fayette. So there was a critical piece of the puzzle we could address.

All the small groups that morning had come up with correct solutions to the problems before them. But to really start teaching subject areas through dialogue, they will need to think about what they can do when the solutions their students arrive at are wrong. They need to learn how to help their students see their own mistakes by posing questions that point them in the right direction.

It is, as they say, “not brain surgery.” In a sense, it is simple enough. They need to learn to ask questions about what they themselves don’t understand in their students’ responses, trusting that such questioning can lead to discovery: their students’ discovery, their own discovery, or both. But until they see examples of such teaching, it will be hard for them to imagine how it works. The temptation will always be to simply tell students that they are wrong, and to present the correct answer, in a manner similar to what they already are inclined to do.