CLM is a comprehensive approach to poverty alleviation. We emphasize helping our members generate reliable incomes, but we aim more broadly. We want to help them improve almost every aspect of their lives. The women who graduate are not simply wealthier than they were when we selected them. They are different. They are confident and forward-looking, health-conscious and well informed.

This transformation involves a lot of learning. We teach them to take care of their assets, of course, and to use those assets to make money. But we also teach them about ten essential health and life-skills issues – like good nutrition, reproductive health, and hygiene – that can significantly improve their families’ well-being.

And that’s not all. Though we are not able to offer comprehensive literacy services, we help the women learn, at the very least, to sign their name. This is less a question of literacy than of dignity. Those who cannot sign in Haiti mark their acceptance of documents with a thumbprint. Though our case managers handle this process as respectfully as possible, it can’t help but be demeaning.

A few can already sign when they join the program, but not very many. And some who haven’t ever been to school nevertheless learn very quickly. Case managers typically make members buy an inexpensive copybook and a pencil. Each week they prepare a page or two of homework for the member by printing her name a couple of times across the top of each page. The member’s assignment for the following week is to copy it on the lines below her case manager’s model, filling up the page. This very simple procedure is enough to get most women signing their name within a few months. They then turn to their husband’s name, their children’s names, or to numbers: whatever interests them most.

But for some women, learning to write their name presents a significant challenge. Copying something as complex as an entire name is well beyond what they can do at first. Case managers start them with a syllable at a time, or even just a letter. And even this can be a challenge for some.

This brings me to Cenicia. Orweeth, her case manager, has been trying, with very little success, to help her write her name for almost six months. The day I visited her with him, she presented him with her well-done homework: two pages of beautiful little c’s. It turned out that one of her children had done the work for her, which only shows that she’s frustrated enough to want an easy way out of the difficulty. When we asked her to make a c in front of us, she couldn’t do it.

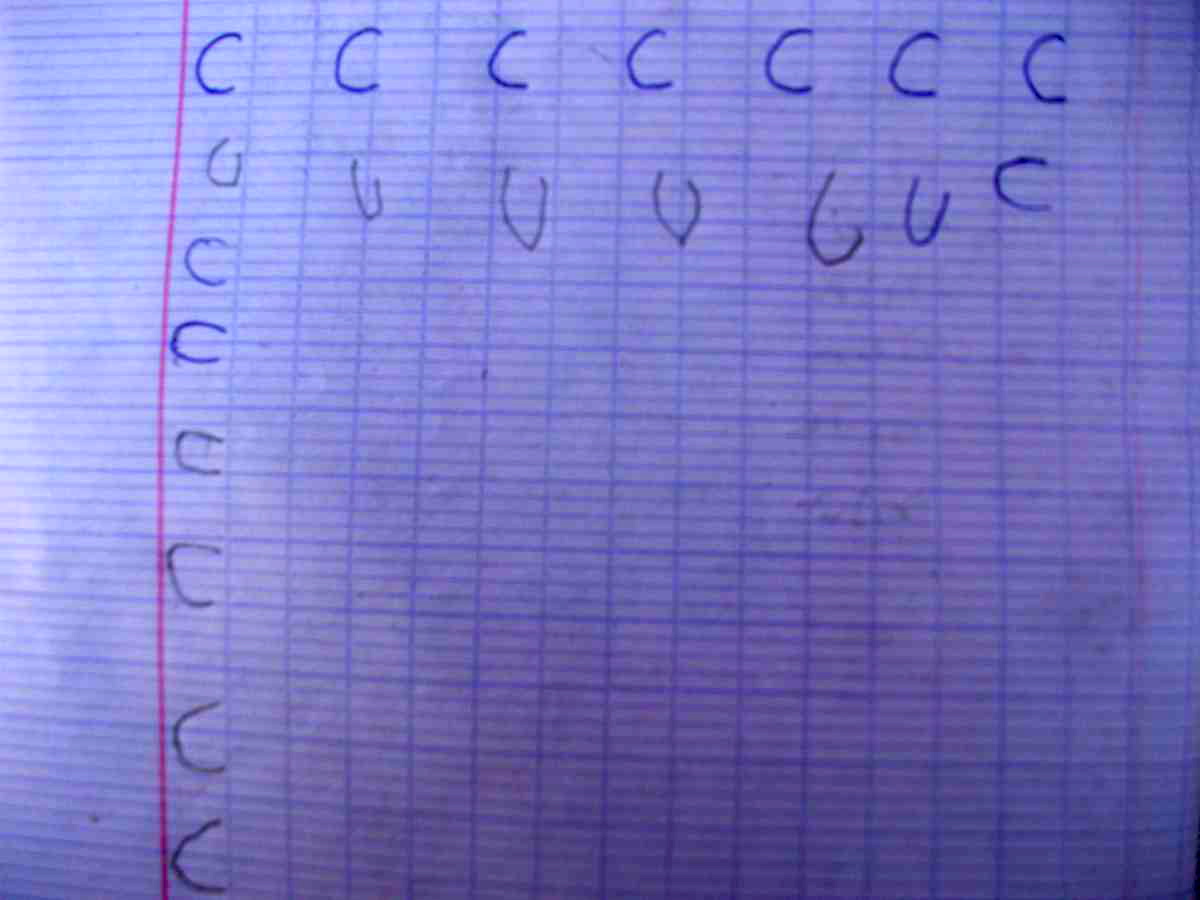

So I decided to sit back and watch as Orweeth offered a writing lesson. He drew a line of c’s across the top of a page, and asked Cenicia to copy one. What she drew looked like something between a u and a v. The second row of letters in the photo below shows what I mean. Each time she put her pencil to the page, she would make a downward stroke, slightly curved, almost like the opening of a parentheses. Once she got to the lowest point of the parenthesis, she would start back upward to make the other side of the u. Each time she started to turn back upward, Orweeth tried to stop her. He apparently imagined that her parenthesis was the c, and that the problem was that she was extending what looked to him to be the bottom part of the c too far, bringing the line back upward. Again and again, he told her with increasing exasperation not to bring the line back upward, not to close the c’s opening. Again and again, she did the same thing. Orweeth wasn’t getting anywhere, but he was getting frustrated, so I asked him to step aside. The photo below shows the work that I then did with her:

As I watched was Cenicia was doing, I made what I thought was a discovery. She was intent on trying to reproduce the c’s half-moon shape. That was, in fact, the way we had been explaining how to make a c: simply trace a half moon. But each time she put her pencil to the page, she made her first move downward. Once she had done so, she had no choice but to turn the line back upwards. Otherwise, the half moon would be incomplete. So instead of telling her to stop turning the line back upwards, I asked her to start by making a line that moved back from the point where she placed it on the page. Having done so, I reasoned, she would be forced to turn the line back to the front, and would thus have her c.

My plan failed. She continued to make little u’s. These are the ones across the second row of the photo. Apparently, my suggestion that she make the first move backwards didn’t make sense to her.

So I thought again for a moment, and then decided that, rather than giving her a new instruction, I would pose a problem. I asked her whether she could see that, while the c’s I made were open on the right, hers were open on the top. They were facing different directions. She said she could see the difference. So then I asked her how she could make her c’s point in the same direction as mine.

Now it was her turn to think. What she then did surprised me. She started her pencil at the rear-most point of the half moon and made the top half of the c with one line. Then she returned with her pencil to the point she had started from, and made the lower half of the c. In the photo, the first one that she made correctly is the fifth one from the top in the left-hand column, and she made all the ones beneath it. We prepared a page for her to do as homework, and we’ll see next week whether she’s on the right track, but she seems to have broken through something that was getting in her way.

Whatever Celicia learned from the experience, I certainly learned more. A human being is not a photocopier. Celicia’s work could not succeed as mindless reproduction. Until she started to grasp the essential points of the simple image we were asking her to make, the task of making even her name’s first letter was beyond her. Time will tell whether I’ll be able to teach Orweeth what I think I learned and whether that lesson, in turn, will help Celicia move forward.

Madolie and her case manager, Sandra

Madolie and her case manager, Sandra Sandra talked with Madolie’s daughter, too. Here she listens, holding her young son.

Sandra talked with Madolie’s daughter, too. Here she listens, holding her young son.

Jackson and his mother, Manie

Jackson and his mother, Manie