Our team first met Christella Fleurissaint in May 2013, when we were going through our selection process for a new group of families. She was living at the time with Rosemond, her second daughter’s father. She had her first daughter with her as well. “My oldest girl’s father has never done anything for her. I have to be her mother and her dad.”

The four of them shared a rented room. Rosemond would do odd jobs. Christella would buy vegetables with money she’d borrow from neighbors and friends, then sell her merchandise and return the capital right away. They owned neither land nor livestock. They had no way to send the girls to school.

But shortly after Christella joined our program, her relationship with Rosemend disintegrated. He was living mainly in Port au Prince, and he stopped coming to see her. Her annual rent was due. It was only about 1000 gourds – about $25 at the time – but she didn’t have the money. And her vegetable business collapsed because she lost the money in the market one day and wasn’t able to pay back the neighbor who lent it to her.

When she joined the program, she chose goats and a pig as her activities. She wanted to get back into the vegetable business as well, but she and her case manager Christian figured that she’d be able to do that with savings from her weekly stipend when she was ready. She wouldn’t need much to get started.

She started dating Michelet, and they quickly moved in together. Michelet had been a hard-working builder, but successive motorcycle accidents had damaged he knee beyond repair. He gets around nimbly with a crutch, but can no longer carry the heavy loads that anyone working with rocks, cement, and cinder blocks needs to manage. So he learned to change and repair flat tires. The highway from Port au Prince to Mirebalais and beyond passes through Labasti, and improvements to the road have come with increased traffic. His services were in steady, if not heavy, demand.

He helped Christella pay the rent she owed and added money from his earnings to grow her business. He also took on shared responsibility for the household. They eventually had a child together, but he showed himself to be devoted to her other daughters as well. “Anytime someone asks him, he says he has three kids.” Christella explains. “You should see how my oldest girl clings to him.”

Thanks to their good care, Christella’s livestock thrived. Her pig grew quickly, and her goats had kids. Soon her older daughters were in school.

But both she and Michelet were frustrated by how limited his contributions to the household were. “Michelet might make two hundred gourds on a good day, but he didn’t have his own equipment, so he’d have to give half to the owner of the tools.”

So they made a big decision. They sold all their livestock and used the money to buy a small, gas-powered air compressor. It cost 14,000 gourds. Michelet’s earnings would double right away. “Christian liked the idea, but he told us to be sure to buy some livestock as quickly as we could. He didn’t want us too reliant on just a few things.” They used some of Michelet’s new income to buy a young sow, and used some to re-start Christella’s vegetable business. She had given it up while nursing their baby. Michelet smiles as he remembers. “The other CLM members in our neighborhood all made fun of Christella when she sold her livestock. They thought she’d never graduate. But now we’re doing better than any of them.”

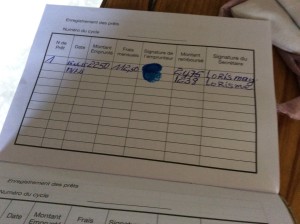

Christella graduated from CLM in December, and immediately joined Fonkoze’s credit program. She likes credit because it gives her more money to invest. The business takes a lot of work. She’s on the road all the time, buying at various local markets and then selling in Port au Prince. “I don’t have a regular place to buy or a regular product. Sometimes it’s okra, sometimes it’s sweet potatoes. Sometimes I buy corn. Whatever I think I can sell.” When she graduated from CLM, she had only 1750 gourds to buy merchandise with, but her first loan was for 3000 gourds, and as soon as she paid that back she got a second one for 4000. She’ll finish repaying her second loan in December and take out a new, larger one right away. “I’ll need the money to buy merchandise to sell for the New Year’s holiday.”

Christella has made enough profit that she was able to buy a second pig. Meanwhile, Michelet keeps working hard. He took his compressor to Saut d’Eau for the parish festival there, which is one of the largest in Haiti, and made enough money to pay a three-year lease on the land their CLM house sits on. Christella says, “There’s nothing lazy about Michelet at all. He’s always working hard.”

And they have a clear goal for the coming years. They own no land, and so can’t really build the home they’d like to live in. “You can’t put a nice house on rented land,” Michelet explains. But thanks to their lease they mow have three years to save up to buy a little plot. “We’ve promised ourselves that we’re not going to rent land any more.”