Enel Jacob

Fonkoze’s team started looking for new CLM members in Ramye in late 2020. At first, Edeline and her husband Enel were not slated to be part of the program. The couple was living with their two little boys, a toddler and an infant, in Edeline’s parents’ home. At the community meeting that produced the first list of possible program members in the area, they were not even mentioned. Their neighbors counted them as part of her parents’ household. They did not think of them as a separate family.

When Fonkoze’s work in the area got going, however, the team met Edeline and recognized her need. Fortunately, the Haitian Timoun Foundation, which was financing the CLM program in Ramye, made a late decision to support 150, rather than 100, families. That meant there was support for 50 extra families, and Edeline and Enel could join the program with that additional 50.

***

Ramye is a small, isolated community just northeast of central Laskawobas, between the downtown area and the Artibonite River. The river is dammed downstream in Pelig to generate electricity, and the dam creates a network of small, irregular tentacles of muddy water, which grow and shrink with the season as rain adds to, and irrigation and drought take away from, the river’s flow. Ramye lies among these tentacles, with water on multiple sides. More sides when the water is higher, and fewer when it dries. At times it is an island, at times just a penisula.

The dirt road that leads towards Ramye is manageable during dry season, but it turns muddy when it rains and therefore slick. It becomes a challenging ride on a motorcycle. Steep in places and rocky everywhere, rainwater has cut irregular traces through the rocks. The road passes between little houses and small fields of corn, pigeon peas, and plantains. Merchants selling small items — like snacks, groceries, or laundry soap — sit alongside the path every few hundred yards, their wares displayed in a basket in front of them or on a small table.

Then the road comes to an end.

During the dry season, it’s just a short walk from the end of the road, across some more fields, to the footpath that winds up through Ramye. In the rainy season, however, these fields flood, and a canoe ferry carries residents and visitors of Ramye across. The driver stands in the back of the canoe with a long pole that he uses to push it across the flood water. Passengers sit on a couple of rough boards nailed across the boat as benches.

***

When they joined CLM, Edeline and Enel had been really struggling. The main source of their income was a series of construction jobs that Enel would take in Pòtoprens. His brother-in-law is a builder who was happy to take Enel onto his team as a laborer, lugging concrete or blocks to the masons doing the skilled work. Enel would have to leave his wife and their boys for weeks at a time, but he was resigned to it. “Things are hard. If you can get a job, you take it.”

Early in 2020, just before they joined the program, Edeline got sick. Their second son was an infant, and Enel was really concerned. “I did everything I could.” Enel took Edeline to two different Partners in Health hospitals, and she eventually recovered. But the couple spent most of their money getting her the care she needed, even though the care itself was almost free of charge.

When they joined CLM, her health was much improved, but the improvement did not last. Edeline grew sicker and sicker until she passed away in February 2021. Enel was left as a single father of boys two and three years old. The CLM team decided to continue to work with him in Edeline’s place.

By this point, the family had moved into their own small house, built with the program’s assistance, on the land that Edeline’s mother gave them. Enel took care of the livestock they received. His close attention to their goats kept them flourishing, even as other goats in the neighborhood suffered from a shortage of food during the dry season. Their pig got sick and died, however, and though they were able to sell it quickly to a butcher, all the money that came in from that sale passed through their hands to pay Edeline’s medical expenses. Burying his wife then forced Enel to take on debt.

After her death, Enel continued to struggle. The best way he could think to earn income would have been to go to Pòtoprens and work for his brother-in-law, but he didn’t feel comfortable leaving the boys or, for that matter, his goats. For a short time, he and the boys depended on irregular charity from his friends.

But then his sister called him. Through her, his brother-in-law was offering him two weeks of work. He didn’t see how he could refuse. He could drop his younger boy off with his mother, who lives down the river from Ramye, near Bagas. The older boy was already in school, so he asked a sister-in-law, who lives next door, to look after him. A local teenager had been sleeping in his home with him and the boys since Edeline died, and that boy would look after the goats.

A life mostly away for his boys was not what Enel wanted, though. He knew they needed him. And he had an idea of a way to start a business that would allow him to live at home. He would buy and sell livestock. He would go to the market in the morning, buy low and sell high. It can be a lucrative business for someone who really knows animals and is a strong negotiator. He could start with chickens, work up to turkeys, and move on to goats when he had enough capital. He is also good with livestock, so he could buy sick, low-value goats, and care for them until they recovered their value, and then sell them.

But just getting started, even with chickens, would take some capital, and after the funeral expenses, Enel just didn’t have it. Going to work for his brother-in-law was a way to make enough to begin, at least in a small way. He was also saving money in the savings and loan association that Edeline joined when she entered the program, but he was afraid to take out a loan. “If something happens to money you borrow, it’s a problem.” And the association wasn’t going to pay out his savings until the end of the cycle.

His desire to start and build a business fit into a larger plan. He was not comfortable living on land that belongs to his deceased wife’s parents, but his in-laws were unwilling to even talk about selling it to him. They wanted to him to think of it as his. They told him that they owed it to their daughter’s kids. But even before Edeline had passed away, he had told them that he wanted to work towards buying the land. He thought of buying a plot of land to live on as a man’s responsibility. And he was not yet even 30. Though his wife had died only recently, he knew that he wouldn’t want to live his life alone. He didn’t think a woman would be willing to move into a house built on his first wife’s family’s land. He wanted to discuss a purchase, but his in-laws just wouldn’t talk about it.

And there was more. He couldn’t see himself wanting to live in Ramye forever. He doesn’t like how remote it is. He dreams of moving with his boys to a house closer to downtown Laskawobas. With its easy access to multiple large livestock markets, it would really help him build the business he was hoping to establish, and it would also mean better schools for his boys.

So, he decided to take up his brother-in-law’s offer of work, but by the time he got to Pòtoprens, the work had been completed. There was no job left for him. He had made the trip for nothing, and when he got back to Ramye, he found his livestock in a bad state. The young guy he had asked to look after his animals had not taken care of them the way he said he would, and Enel didn’t really blame him. Living under Enel’s roof, the kid expected Enel would do more to keep him fed, but Enel just wasn’t able to. He was much more focused on looking for odd jobs than on helping Enel.

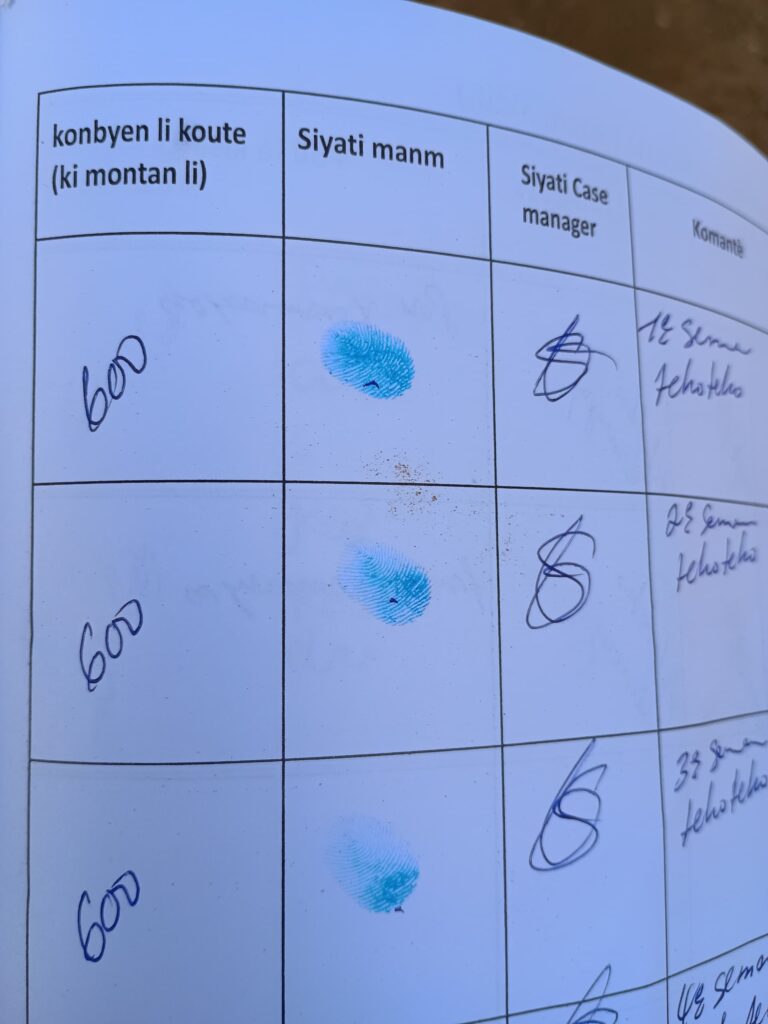

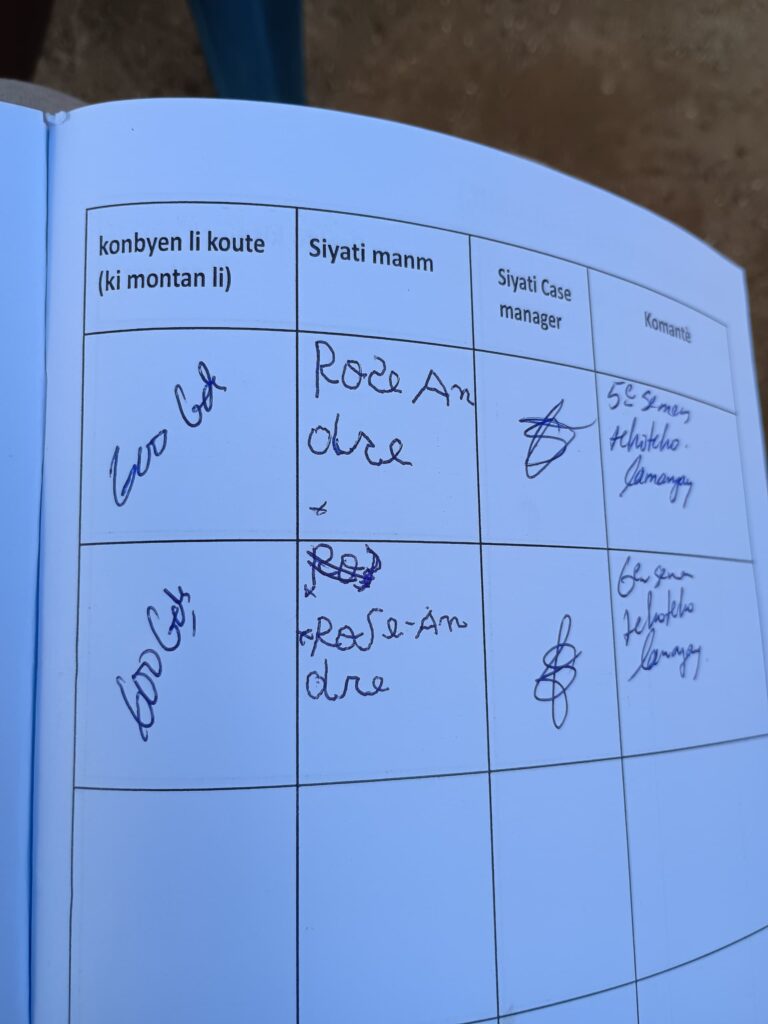

Fortunately for Enel, because of the CLM program, there was at the time a fair amount of construction going on in the neighborhood. And though he couldn’t get a job as a homebuilder, he could get hired to turn palm trees into the planks that local residents use to wall-in their homes. The job typically paid 1750 gourds for a tree. Enel didn’t get a lot of those jobs, but he got some. “I would save 250 gourds each week in my savings association, and if I had been paid for a tree, I’d take 500 to the meeting instead of just 250 and leave 250 in the VSLA’s box.”

That way, he would be ready even if he wasn’t able to save anything the next week. But as local CLM-funded construction neared completion, those jobs dried up, and so Enel made his next plan.

Settling back into life in Ramye, he began to do well, but not spectacularly well, with his livestock. Fonkoze had given Edeline and him two goats, and he turned them into five. One of the two he received had a pair of kids, and he bought an additional adult female himself. The other of the two he initially received returned to health once Enel took it back under his own control after his return from Pòtoprens.

Purchasing the extra goat took smarts. Enel had received cement from the program to build up a small protective barrier around the base of his home’s walls, but it was too little to do the job. Rather than waste it with a useless half-measure or let it harden in the sack while he saved up to buy the rest of what he’d need, he sold it and used the proceeds to buy the goat.

The useless trip into Pòtoprens had convinced Enel that he was better off creating an activity near his home. It wasn’t a simple matter, but he started finding more things to do because he wasn’t particular. One moment he was fishing in the waters around Ramye, selling his catch to merchants from downtown. Another moment, he was collecting driftwood to make charcoal. He would rent himself as a laborer to builders. When he could find nothing else, he would simply sell a day of farm work to neighbors.

He eventually earned enough from these odd jobs to buy a small bull, and when the bull became a lot to handle, he sold it and bought a heifer instead. “The bull wasn’t going to reproduce, and it had begun chasing people.”

He also went back to his plan to buy and sell livestock. He finally assembled the capital that he needed to start his business by cutting down the trees on a small plot of land and turning them into charcoal. He produced five sacks, which he sold for 750 gourds each. It was enough to start buying chickens.

Enel would hang out on the roads leading to a market, stopping folks on their way. Some people were happy to give him a deal on animals they were bringing to market in order to avoid the need to go all the way to market themselves. It would save them time and effort. His willingness to spend his day buying and selling was his superpower, and he began earning enough to take care of his kids and to contribute to his VSLA each week. He eventually borrowed 5,000 gourds from his VSLA to add to his capital.

He was always careful about his expenses. “If I have five gourds, I know I won’t waste any of it.” And, so, his capital slowly increased. Before long, he had enough to buy goats, rather than just chickens. He also joined a second VSLA. “I could see that VSLAs are good for me. They force me to save. If I tried to keep money in a box, I would always find ways to spend it. The only way to take money out of the VSLA before it’s time is to take a loan.”

One day, just after he crossed the water heading out of Ramye on his way downtown, he saw a sign. A woman just across the water was selling land. The sign listed a phone number, and he called right away. He made a date to see the land and speak with the seller. He asked the secretary of his VSLA to go with him. “I had no experience with land.” They negotiated a sale price of 220,000 gourds. Enel sold his cow — it was pregnant by then — and a large billy goat that had been produced by a nanny that the CLM program had given him. He also borrowed 25,000 gourds from his VSLA and added the capital from his business. In all, it was enough for a 150,000-gourd downpayment.

It put him well on the way to achieving his biggest goal. He had already used his savings at the end of the last cycle of his VSLA to begin to collect home construction materials. He would disassemble the home in Ramye and reconstruct it on the new plot, covering it with new roofing.

But the purchase created problems, too. It ate up the capital in his business, so it eliminated his primary income, and he still had himself and two boys to take care of, a VSLA loan to repay, and regular contributions to his two VSLAs to make. He went back to doing odd jobs. He will be able to pay back most of the VSLA loan out of his savings when the cycle is complete. But he’ll have to add earnings from his odd jobs to finish repaying.

He continues to contribute to both VSLAs. Once he pays of his debt in the one, he can start thinking about whether to use a loan from the other to restart his business. He still owes 70,000 gourds on the purchase of land, however, and it will take a lot of work to clear that debt.