Murlande Mauralien lives in Fon Pay. She and her older sister, who is also a program member, each have their own small house in the yard that belongs to their parents. She lives with her husband Claudet and the couple’s two children.

Murlande has always been the family’s most consistent earner. Claudet takes small jobs around the neighborhood when he can find them, and those jobs can bring in more than Murlande’s work does, but only when he can find them. Murlande goes to downtown Bonbadopolis every market day, where she sells laundry products: soap, detergent, bleach, etc. She buys what is now about 5,000 gourds worth of product when she gets to market, and sells it by carrying it around the market with her, calling out her wares.

She’s been running the business since she had her first child, and she thought of the business model herself. “When you are bringing up a child, you look for a way.”

She had a serious problem to overcome. She had no business capital. So, she would go from one of the larger merchants to the next, asking them to sell to her on credit. She would bring them their money at the end of the day. It would increase their sales effortlessly if they could trust her. For her part, she’d make a little profit that she could spend on groceries that she’d take home at the end of the day. But she could never get ahead. There were just too many expenses to manage with very little in earnings.

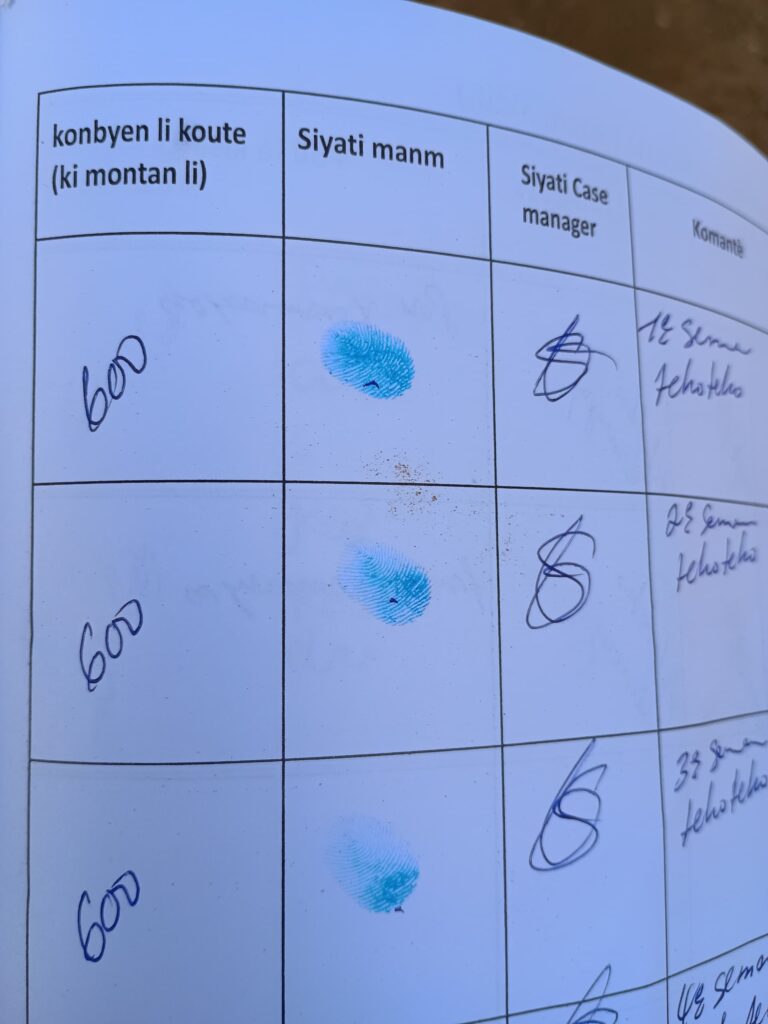

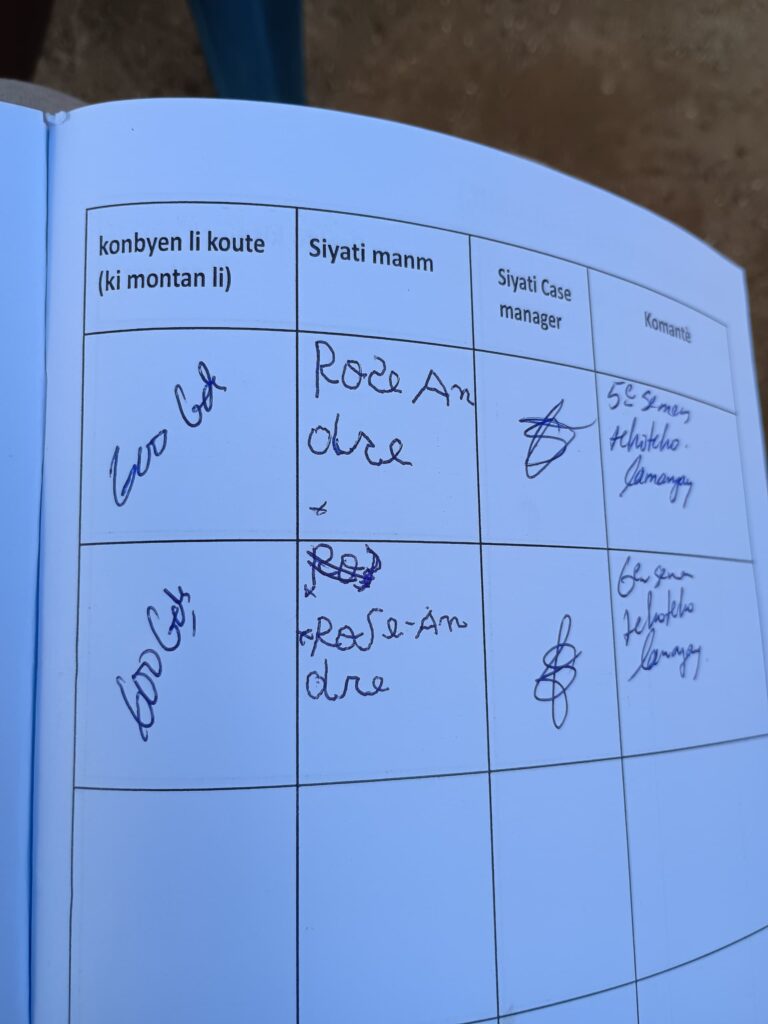

She joined the CLM program, and things have started to change. She has been part of a savings group, and has been buying five 100-gourd shares at every weekly meeting.

This is extraordinary. While it is true she has already received 2,000 gourds in cash stipends, it is hard to imagine her simply saving all of it, and even if she did, she’s already bought more than 2,000 gourds of shares. When asked to explain her success, she says two things. First, that she never had a way to save. But she also points to the training that she’s received from program staff. “They taught me to focus on the profit I make and what I should do with it.”

When she was ready to receive her first transfer of business assets, she could have chosen to invest in her business. She could switch to buying merchandise with her own money or add more merchandise beyond what she gets with her credit. But she didn’t. She plans to do that when she receives the second part of her transfer, but with the first she bought two goats. She hopes they will produce offspring and that eventually she’ll be able to buy her own plot of land.

Guerta Augustin lives with her husband Talus and five of their six children in Bwa Nèg, in Bonbadopolis. She has two older children from a previous relationship. Her oldest daughter is married, living with her own husband, and her second lives with Guerta’s mother. But neither lives far, and Guerta sees them both often. Guerta sent one of her girls, a twelve-year-old, to live with her sister-in-law when that woman became pregnant with her first child. The woman asked Guerta to send her niece to her. She needed help. Guerta understand’s the woman’s need, and she is happy about the way she treats Guerta’s daughter, so for now just the seven of them are at home.

Talus was once the main earner in the household. Guerta describes him as a hardworking farmer, and he would farm their own small plot of land, but he’d also work also for their neighbors. But he broke his arm badly, and though the break healed, he can no longer do heavier tasks. He gets fewer, smaller jobs working for others even as the couple’s own crops have been decreasing. Guerta’s income became more and more important to the family.

She’s a weaver, making sleeping mats and other products out of the leaves of the latanyè, a variety of palm that grows like a bush, low to the ground. More important for her income than sleeping mats, are the saddles she makes, mainly for donkeys and motorcycles. These saddles are used mainly to load five-gallon jugs of water for trips to and from the water sources scattered around the area. The saddles are important for local life, and there is always a market for them. Most are sold even before they are finished. But they involve a lot of work. With her household chores to do as well, she needs three to four days to produce just one. And even the larger ones, for motorcycles, sell for just 400 gourds, or about $3. Those for donkeys, for only 250.

Home itself is a problem, though. They used to live with Talus’s parents, but his siblings were consistently unkind to Guerta. The couple was made to feel unwelcome, so they had to move away. Without a home of their own, they talked to a man who had abandoned his late parents’ home to move into the one he built with his wife. They asked whether they could use the parents’ empty house. The man agreed, and they have been living there for four years, but the man’s wife and his siblings have never been happy about the arrangement, so Guerta would like to move as soon as they can. “Even if we have to build on land we can farm, I want to have my own house.”

As much as Guerta needs to increase her income, you might expect that she’d use the first investment funds that the CLM program would transfer to her to create a small commerce. But that isn’t what she did. “I can’t have a commerce without a home.”

She decided to buy goats instead. “I wanted to buy goats because I didn’t want the money to just pass through my hands.”

And she got lucky. The day she went to market with her case manager, she found someone selling a mature nanny with two young female kids, not quite weaned. She was able to buy all three.

Within a few months, and with a little luck and a lot of attention to her animals, she could have three fertile females reproducing at once. She and Talus have already begun assembling the lumber they will need to build their home, and the goats may quickly help them buy the rest that they lack. But her real plan for the goats is to use them to take care of the regular expenses she encounters, school fees and the like.

She hopes to be able to start a small commerce once she has a home to put merchandise in. But she has another transfer of investment funds due to her, and her case manager might need to talk with her about the sorts of businesses she could try even before she has a place at home to store any wares.